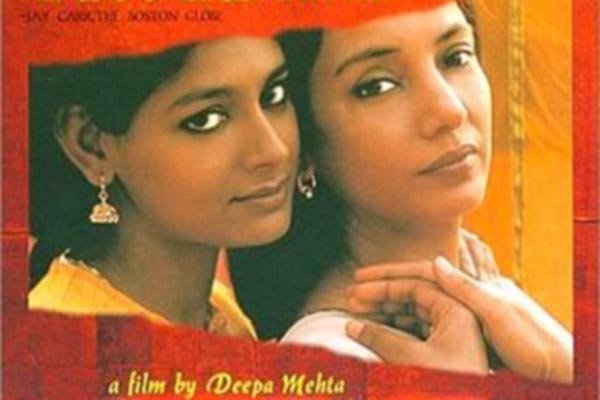

Fire (1996), dir. Deepa Mehta, is an Indian-Canadian romantic drama infamous for being one of the first explicit portrayals of homosexuality in Indian cinema. The plot follows Sita, a young woman recently arranged married to Jatin, a DVD rental store owner, who marries Sita to appease his traditional family while still keeping a relationship with his girlfriend. Sita, isolated, finds comfort in her sister-in-law, Radha, who is married to Jatin’s older brother, Ashok, a celibate religious zealot who guilts and controls Radha throughout their marriage. Both Sita and Radha fight against the patriarchal standards of Indian society that bind them, and fall in love in the meanwhile.

The primary impression this film left was that, despite everything, it’s not a lesbian movie. There are lesbian elements; the plot revolves around the radical lesbian coupling of two women navigating Indian patriarchy, but it’s still not a lesbian movie.

Sita and Radha’s desertion of their husbands and finding love in one another is a physical representation of their mutual eschewal of Indian patriarchal standards. Both husbands portray a trope of masculinity, each with his own facet of misogyny. Jatin represents the sexual freedom permitted to young Indian men but repressed in Indian women; his mistress is an open secret, and he sells pornography under the table at his store. Ashok, on the other hand, is completely celibate, reflecting the teachings of his conservative swami. He denies Radha sex, and controls her sexuality by guilting and isolating her in their marriage.

Mehta uses lesbianism as a vehicle with which she addresses the misogyny in Indian patriarchy, but does not make it the subject of the film. What exactly makes a lesbian movie? Intimacy, for one. Not just the inclusion of a sex scene, but scenes in which the audience could feel the electrecity, the chemistry between the two leads through the screen. (Side note, the fact that Mehta managed to include one, considering the dual oppressive forces that are Indian censorship laws along with the cultural taboos of sex, impressed me quite a bit.) These intimate moments were there, admittedly, but so scattered and sparse that it didn’t seem significant – or at least, the most significant.

There were two key scenes, however, that truly encompassed that intimacy. The first, when Sita asked Radha to oil her hair, and the second when Sita and Radha danced to an old Bollywood song.

In South Asian communities, the thickness, length, and quality of a woman’s hair is one of the foremost standards of beauty. Though both genders do oil their hair, the practice is traditionally associated with womanhood, and passed through generations between female relatives. Direct contact with another woman, massaging oil into her scalp, establishes a connection, an intimacy. The context of this intimacy is transformed when Sita asks Radha to oil her hair; the tradition goes from familial and feminine to romantic and sensuous. This subversion of a traditionally feminine practice which exists to enhance a woman’s beauty to a man, to a ritual of homoerotic intimacy between two women, establishes a particularity to their relationship within the South Asian context. It demonstrates a potential expansion of relationships between women while also reifying traditional Indian femininity.

The dance scene between Sita and Radha also achieves a similar form of intimacy. Sita dons Jatin’s suit and forgoes the conventions of Indian femininity, while Radha lets down her hair, previously tied to match her husband’s austerity, and reclaims her femininity within a lesbian context. Their dance together evokes butch-femme imagery, a nice, if brief, nod to actual lesbian culture. The song that is playing is classically Bollywood, a stereotypical duet between the hero and heroine; Sita and Radha, by assuming the roles of these heterosexual stock characters, queer an essential aspect of Indian culture, and reclaim it for their own homosexual love.

If the movie had dedicated more time to exploring lesbianism itself within Indian culture and patriarchy, and had incorporated more tender moments between the two main characters, I would classify this as a lesbian movie. Unfortunately, Mehta was much more focused on critiquing Indian culture in general; the plot was a patchwork of issues, ranging from the main conflict with Indian patriarchy, to rising religious fanaticism (Ashok’s storyline), xenophobia against immigrants (Lisa, Jatin’s mistress, is ethnically Chinese), to even abuse of elderly invalids (though unfortunately played for laughs.) It synthesizes into a hurried, almost haphazard film, which, combined with the slightly wooden acting, did not sit well with me.

Mehta uses lesbianism as a device, an object rather than a subject, to arouse discussion and make a statement about Indian misogyny. Though a great effort in itself, the film in my opinion does not meet the expectations of a lesbian audience. I, as a South Asian lesbian watching this film, though happy for some sort of representation, did not feel my experience reflected or validated within this film, and it’s that lack of relatability, of insight into the lesbian experience, that depreciates my enjoyment of the film.

In conclusion, 6.8/10 stars.