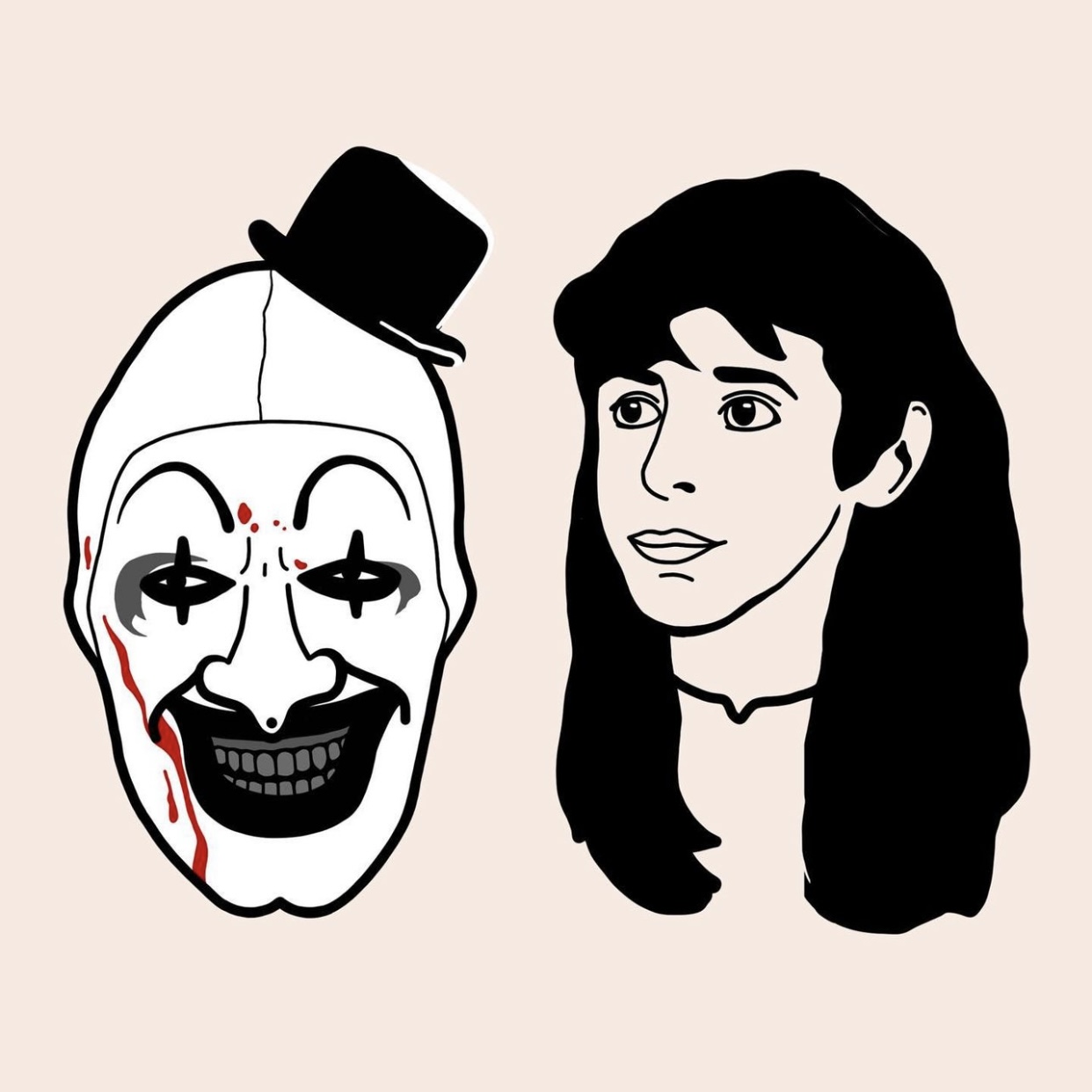

Illustrated by Christopher Ikonomou/OutWrite

This article was originally published in our Fall 2022 print issue “Satanic Panic.“

Content warning: violence, rape/sexual assault

The horror genre has a transphobia problem.

I’m an avid horror fan whose apartment requires a warning to enter with all the horror villains plastered to my walls. I am also a transgender person who knows that negative depictions of my community, however unintentionally harmful, do have an impact. To understand these consequences, I will be discussing four horror films that feature transmisogynist tropes and explore how their portrayal causes real harm to the trans community.

Spoiler alert “Sleepaway Camp” (1983), “Insidious 2” (2013), “Terrifier” (2016), and “Silence of the Lambs” (1991)!

One way to discuss the effect of media on our real lives is through cultivation theory, the idea that we learn things from entertainment that we take to be reality, and as a result they inform our reality. For example, research such as a 2016 study found the portrayal of gender norms and rape myths (such as victim blaming) in sitcoms like “Parks and Recreation” perpetuated participants’ real attitudes towards abortion and contraceptives, especially for those who already held some misogynistic beliefs.

So why do fictional portrayals of trans people matter? Simply put: because they’re killing us. Violence against trans people, particularly trans women, has been rising steadily for years, while hundreds of anti-trans laws are being proposed across the United States. If media has the opportunity to influence attitudes towards a marginalized group, I’d rather it didn’t equate non-cisheteronormative gender expression with mass murderers.

Perhaps the most famous analogy to transness in horror is the character Buffalo Bill in “Silence of the Lambs.” Buffalo Bill is a serial killer who kidnaps and tortures women before killing them and wearing their skin. I went into this film with an open mind, only to cringe when the word “transsexual” is used several times. In addition, Hannibal Lecter, an institutionalized cannibal psychiatrist, mentions how Bill requested and was refused hormone replacement therapy and sex reassignment surgery several times. However, Dr. Lecter insists that Buffalo Bill is not “truly transsexual,” a point that’s affirmed by most horror fans when this topic comes up. If Bill’s gender is unimportant, then why is transness directly referenced in the film? Why do we watch the serial killer dance around wearing women’s clothes and makeup? If you ask those same fans, they’ll answer that it’s a detail to show how deranged Bill is, but the idea that “men dressing as women” are unhinged does not exist in a vacuum; it implicitly links trans behavior to violence and perpetuates pre-existing transphobic beliefs past the point of fiction. We’ve seen this idea come to life in cases like Sabrina Prater, a trans woman whose viral TikTok of her dancing in a run-down house led to murder accusations, Buffalo Bill comparisons, and doxxing.

This transmisogyny is present in many popular horror films. In “Terrifier,” an infamous grindhouse film, killer Art the Clown wears a woman’s scalp and cut-off breasts while dancing around in an absurd performance of femininity. Why? Because men performing femininity is weird and disturbing! You’d think we could forgo the morbid drag and be convinced of his irredeemability when he saws a woman in half from vulva to skull.

In less literal depictions (and by that I mean no one’s wearing anyone’s skin), there are films like the cult classic “Sleepaway Camp.” The story follows a teen named Angela at summer camp. The audience learns that she lost her family at a young age, so she doesn’t talk much. She then experiences attempted rape by a pedophile, constant bullying from fellow campers and counselors, and repeated sexual coercion by a boy, Paul. One by one, each of the perpetrators are killed in grotesque ways (‘penetration with a hot curling iron’ grotesque). At this point in the film, I’m rooting for the killer; many queer people are attracted to the horror genre because we see ourselves in the monsters, and this was a perfect example. In the final scene, Angela decapitates Paul, but the “big” plot twist is… that she has a penis. A shocked counselor gasps, “She’s a boy!”, addressing the “head” that had fallen in her lap (but not the right one in my opinion, pun intended). We learn that her divorced adoptive mother forced her to secretly transition because she had always wanted a daughter. (A woman who goes crazy after a man leaves and then defiles a little boy with femininity? It’s a twofer!)

Yet another example comes from the supernatural flick “Insidious 2.” In the previous installment, the leading man Josh saves his son Dalton from the film’s demon/ghost dimension and becomes possessed by an old woman’s spirit. We learn that this ghost is not a woman at all, but a man named Parker Crane, a serial killer who murdered 15 women. The only times we see Crane, other than as a scary ghost, are when he’s hospitalized for attempting to castrate himself and in scattered close-ups of him putting on a black wedding dress and lipstick in front of a kidnapped future victim. Similar to the plot of “Sleepaway Camp,” we learn that he grew up with an abusive mother who forced him to be a girl. It’s also implied that Crane gains sexual gratification from this ritual of crossdressing and murder (similar to Buffalo Bill). How does a boy who hated being a girl become a man who dresses up as a woman to kill women for sadistic, sexual purposes? If you think too hard, the aforementioned idea that transfemininity and crossdressing are inherently horrifying rears its ugly head.

In the end, transness is demonized. The issue becomes a positive feedback loop: writers infuse their implicit, transmisogynistic biases into their work, so viewers begin to associate transness with those negative tropes, strengthening the link between transfemininity and horror and inspiring future writers to begin the cycle again. We perpetuate the idea that trans women are predatory men wearing a woman’s appearance (her skin), like a disguise for nefarious purposes. This terror bleeds into reality, and real trans women pay the price. A 2012 study by GLAAD found that in shows with trans representation aired in the previous decade, trans characters were cast as villains or killers in 21% of episodes on every major broadcast network and seven cable networks. Experts like Brennan Suen from Media Matters for America trace responsibility for transphobic attacks largely to media portrayals of trans people, stating, “When you ‘otherize’ them, villainize them and portray them as criminals, it does get ingrained in the culture.”

So, horror writers, please stop using our identities as your next scare factor. If the only way you can think to make your character unnerving is making him a man in a dress, maybe go back to the drawing board.

Credits:

Author: Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

Artist: Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

Copy Editors: Jennifer Collier (She/They), Bella (She/They)