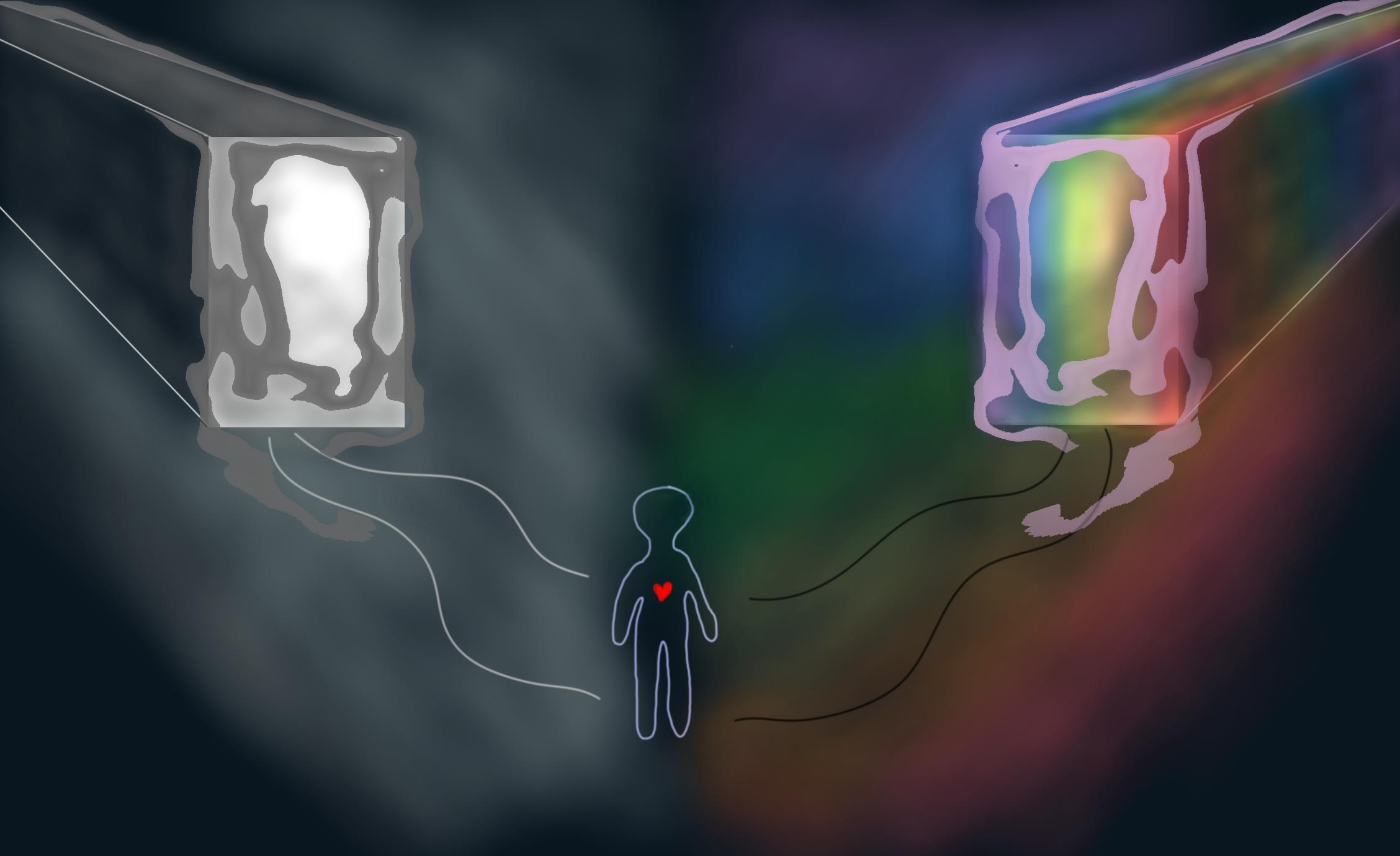

Graphic by Ria Kotak

“Coming out” is one of the most commonly recognized aspects of the queer experience. It’s a moment that’s defined by the reactions we get (whether or not our family and friends accept us, what happens afterward, etc.) and is generally made out to be a turning point in most queer people’s lives. With such high expectations, it’s understandable how stressful it is for so many people, even if it goes well.

The question of whether or not to come out isn’t simple to answer, and many folks have reasons to remain closeted in certain settings. For a lot of us, family is the biggest obstacle.

Alexis, a previous Copy Chief at OutWrite, was raised in a conservative Catholic household. Back home, marriage was only deemed to be between men and women, and homophobic jokes were considered acceptable. Surprisingly, when I asked her what the main obstacle keeping her from coming out was, she didn’t mention any of these things.

“For me, a lot of it is financial security,” she said. While she has a job and pays most of her expenses, she’s likely going to be living with her parents for a short while after she graduates. “I don’t want to feel any resentment or uncomfortableness daily as a result of coming out,” she continued. “I don’t want to burden my family with that constant exposure to something that might disappoint them, nor do I want to confront that daily disappointment.”

For Alexis, leaving UCLA means potentially leaving the on-campus queer community behind. Since her identity doesn’t come up much beyond OutWrite and other queer student organizations, this worries her.

“It’s hard to feel proud of your identity when you keep it hidden.”

Being straight passing — assumed straight when you don’t fit cisheteronormative stereotypes of queerness — can effectively put you in a closet by proxy. When people don’t fit the stereotypical image of a queer person, people generally assume they’re straight. In addition to creating a fabricated standard of “queerness” for other folks to live up to, this complicates the idea of being “out.”

Eric, a close friend of mine, doesn’t fit the stereotype of the flamboyant gay man. Living with his partner and fully supporting himself, he’s in a similar financial position as new college graduates like Alexis. Although he’s doing much better since leaving home, there are still ups and downs. Working jobs with his partner is risky, and it’s not only because of the legislation surrounding workplace relationships. The industry he works in, like many male-dominated fields, is rampant with both internalized and explicit misogyny and homophobia, keeping Eric firmly planted in the closet most of the time.

Even in environments that aren’t so toxic, Eric isn’t super vocal about his identity.

“It’s not that I don’t feel safe,” he said, “it’s just that it doesn’t really matter 95% of the time.”

Outside of queer spaces, sexual and romantic orientation is rarely discussed, a major factor in why many people feel so isolated as they explore their identities in cisheteronormative environments. Eric lives in an area that isn’t hostile to queer people, but many others in Alexis’ position are concerned that they won’t find such accepting communities once college is over.

Being bi, gay, or a lesbian is something most non-queer folks can usually understand without a lot of explanation; other identities, especially those involving gender non-conformity, can often turn into hour-long seminars. This is often made worse because some of us don’t know exactly what— or who— we are, making an already complicated subject even more confusing and stressful for everyone involved.

Martha, OutWrite’s Editor-in-Chief, uses many different labels that fall under the pan and trans spectra. While they’re confident in who they are, explaining their identity poses a bit of a challenge. For Martha, the act of explaining their identity involves so much labor that it’s tough for them to even think about coming out. Back in high school, during a GSA club meeting, just being asked what their pronouns were for the first time caused them to break down; they didn’t know what to tell people.

In a lot of queer spaces, there is a general assumption that everyone is already out or planning on coming out eventually. This, in combination with the common belief that coming out is a necessary component of the queer narrative, causes many folks to feel guilty for not wanting to.

According to Judah, a fellow staff writer for OutWrite, “You don’t owe anybody an explanation; you should be able to be who you are without having to proclaim it.”

To Judah, the process of coming out results in alienation rather than inclusion. This concept, they said, is reflected in media involving queer subject matter like “Love, Simon”: in the show, coming out is presented as a weight being lifted off of Simon’s chest (“You can exhale now, Simon.”). Judah doesn’t see that as liberation or even adequate representation. They want to encourage queer folks to go against the grain, creating counternarratives to heteronormative conceptions of coming out.

“Real liberation would be having the choice to come out,” explained Judah. “There’s so much pressure to be out that it puts a spotlight on people who don’t really want it. We should start owning who we are without having to explain ourselves.”

While it sometimes feels good to express to others what’s going on with us and what they can do to help, it’s unhealthy to reinforce the idea that this is just another item on some kind-of queer bucket list.

Fluidity is a huge part of my experience, so my queerness has been mostly defined by a state of confusion. Because my gender, sexual, and romantic identities are less concrete than a simple “I am a man” or “I like women,” it’s sometimes challenging for me to identify with a label or explain myself using accurate terminology. Sometimes it’s tough for me to believe that I am non-binary, pansexual, or whatever it is I feel comfortable with at the time; in those moments, I have to go through the process of rationalizing why I am who I am to myself. How is someone like me supposed to live up to the standards of other coming out stories if I’m not done understanding my identity? Why do I need to worry about whether or not other people know what I am?

To me, “When are you coming out?” sounds eerily similar to “When are you gonna get married?” Neither question is inherently malicious, but they reinforce the idea that the experience of womanhood or queerness is a rigid path with a set destination. Creating narratives about what people should want stifles individual autonomy, and it’s something we should avoid as a community. Our experiences shouldn’t be compared to a list of expectations — we’ve had enough of that at the hands of cisheteronormativity.

Coming out can be an empowering experience. Making the choice to declare who you are can be risky, and when it pays off, it’s an incredible relief. If that choice is anything less than completely voluntary, however, it’s not serving the same purpose. When coming out is turned into an obligation, it becomes suffocating, not liberating.

Not everyone wants to come out, and there’s plenty of good reasons why. It’s okay if people want to stay closeted in some spaces or be completely private about their identities. By promoting the idea that coming out is a choice, we can create a more inclusive narrative about the queer experience based on autonomy, individual expression, and diversity. Just because someone doesn’t want to come out doesn’t mean they have nothing to say.