Graphic by Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

Hola, mija.

The tinny speakerphone rings through our shoebox apartment; I look up at the sound and see that a work week’s worth of tension has melted from my mother’s shoulders now that she’s heard my grandmother’s voice. Every Sunday evening, she catches up on all the phone calls that she’s missed while working more hours than she sleeps, and she always saves grandma for last. I hope when I’m older, you guys love me like I love my mom, she once told me and my sister, and with an exaggerated swoon I yelled, ay, la drama! and the laughter saved us from having to admit that we already loved her more.

Gracias a Dios, todo está bien.

When we were kids, my parents would take my sister and I to Catholic church services every other year; it was never a special date, just a day when my father would wake up gripped with fear for our mortal souls and say, Vamanos, niñas. My eyes would flit from pew to pew, and I’d watch in awe as everyone around me was possessed with a nearly tangible devotion that I couldn’t begin to comprehend. I had never given much thought to religion, but in those moments, it seemed like the world was coated in divinity.

Then the service would end, and on our walk back to the car, I’d hear conversations like a woman whispering to her friend, Oyiste que el hijo de la Mayra es gay? and the response, Pobrecito, el Diablo lo tiene. Divinity faded from the world, but it stayed in my sister’s laugh echoing during our car ride home, in the twinkle of my father’s eyes when he asked if we wanted ice cream, and in the way my mother wrapped me in her arms when I told her that I needed to talk to her about something that she might not like.

Y cómo están las niñas?

The conversation quickly turns to us, the children born bearing the weight of being the physical manifestation of that better life my mother left El Salvador to chase. To grandma and the rest of our extended family, we only exist in secondhand stories and pictures of family trips to the county fair, birthdays, and graduations. It was never safe for us to travel to El Salvador alone, but visa red tape and seemingly endless wait lists kept my parents from traveling with us for most of our lives. By the time that we could, we were all too swept up in school and work to travel at all.

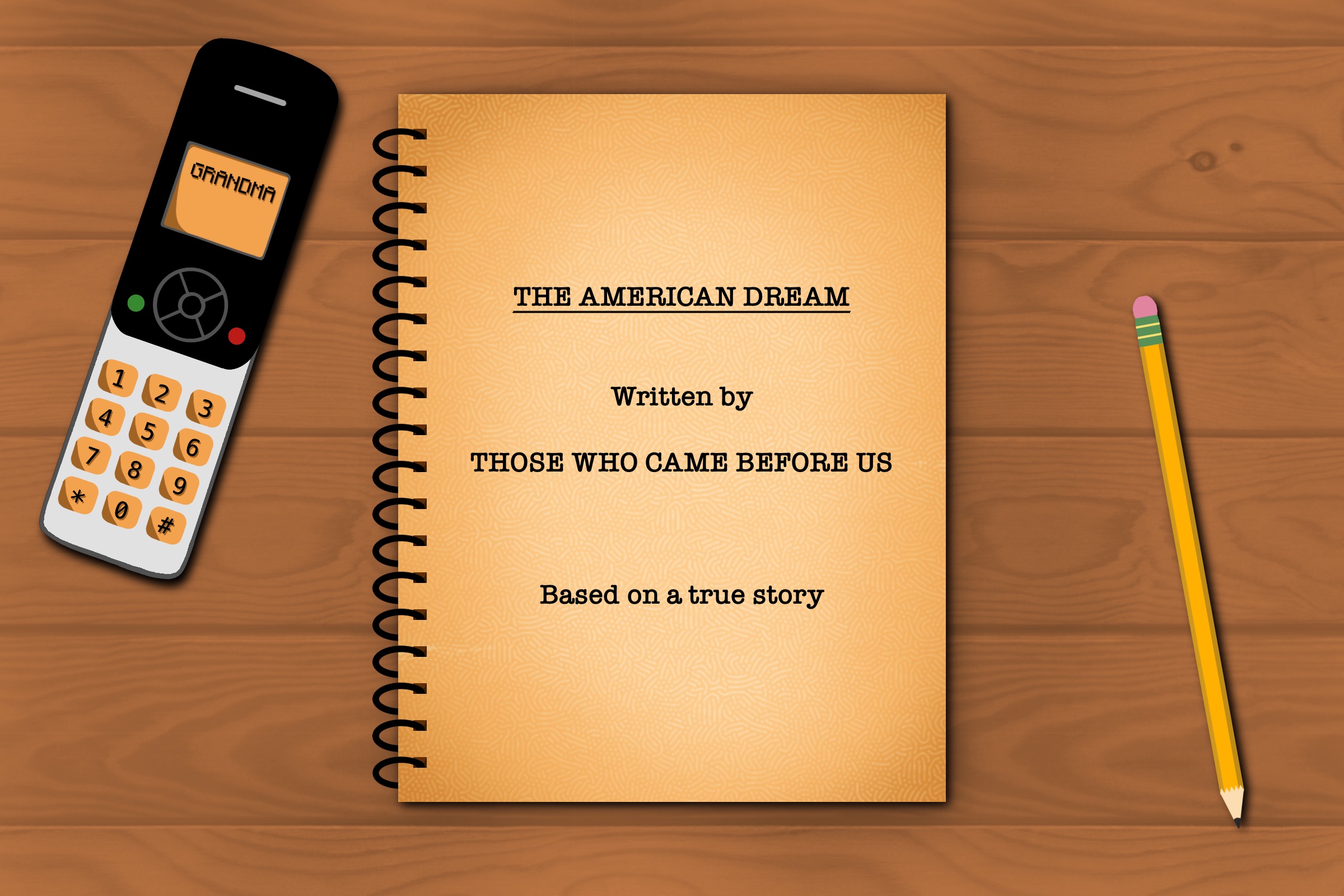

The script of the American Dream called for an education, a successful career, and a relationship with a man that would lead to us ushering in the generation that would carry on the dream for all of us. The reality of it is one daughter who shines so bright that nobody notices that the other is an ever-fluctuating mix of daughter, son, and alien creature that only learned to be human through binge-watching “The L Word”.

Ya tiene novio?

Mom laughs and waves the question off with a, No, she’s too busy with school to think about things like that, and before another question can be asked she continues with, Her father’s so proud of the grades that she’s getting, and she wraps it all up with, Let me tell you about the classes she’s taking. It’s a practiced redirection that has yet to fail given that the concept behind the dream itself is the idea of opportunity. My education shows that it was worth my mother leaving her home at seventeen, worth her not seeing her own mother again until she was forty-one, worth my grandmother only meeting her grandchildren when they were full-fledged adults. My education masks all the other ways that the dream is incompatible with my own, and the truth that I will not shrink myself to make room for the ideas my blood has dreamt up.

Cómo está creciendo!

Redirection is a shield that weakens with every question dodged, and the strength of our defense diminishes further with each year that I don’t show progress towards that husband and child that they say will make me whole. Right now, the shield protects us from the consequences of who I’ll love, but I know the day will come when my love will not be a hypothetical, but the home I find inside her laugh or the moment that I look into their eyes and know. I’ll hear the bells ringing inside my ears, and watch the countdown to the bomb that will go off the second grandma asks, Ya tiene novio? and my mother decides that the truth of her youngest child’s love is not something that she wants to hide.

And I mourn my own dream of my grandmother teaching the little grandchild I never got to be to make tortillas, saving me the burnt edges of a pupusa because she knows I like them, and whispering to me that she can’t wait to see me next summer. Had we been able to have those moments, maybe she would love the truth of me as much as she loves the stories. Maybe I would have torn up the script a long time ago.

Credits:

Author: Lorely Guzman (They/He/She)

Artist: Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

Copy Editors: Emma Blakely (They/She/He), Bella (She/They)