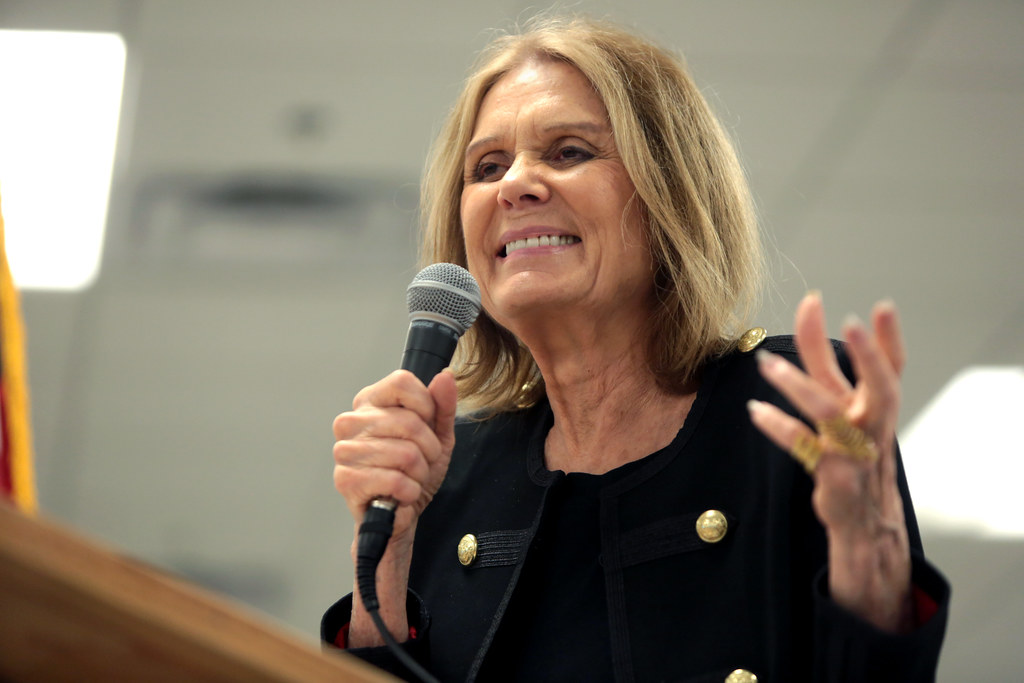

Photo by Gage Skidmore/Flickr

On October 7, 2012, Gloria Steinem came to UCLA to offer a lecture called “Women’s Bodies, Women’s Votes,” and, amidst the crowded hall in Broad (one which she would comment later as disliking—as she does many of the places she lectures—for its inherent hierarchical (and thus inherently patriarchal) structure, a kind of nostalgia for the world of women’s circle meetings), and I was lucky enough to attend, and to be amidst the unanimous standing ovation the moment she walked through the hall, fifteen minutes before she’d even stepped on stage.

But from the moment she did, it was clear she held her audience captive. One of the most utterly remarkable aspects of her presence was her age—in fact, when she mentioned the fact that she was seventy-eight, the guy sitting next to me turned and asked, in absolute awe, “Seventy-eight? She looks like she’s fifty.” Much of that, I think, is due not simply to the way she looks but, almost tangibly, to the power of her energy. She is radiant with it—and after so many years of struggling for rights that have been even longer in coming, it’s a wonder to me she isn’t more visibly world-weary than the average person.

But her rhetoric was that of someone who has not stopped—and perhaps could not stop—fighting. She told the audience some of the responses she’s been receiving throughout the country, one of the most common being why are we still talking about this?—because surely by now a woman’s right to choose should be apparent. But her response was a shake of her head. “I don’t think you understand how revolutionary this is,” she told us. “We are seizing the means of production.” And then, with a laugh, “See, it even sounds revolutionary!”

It was clear from the beginning that this was not a speech intended for griping; it was a speech intended just for that—revolution. She provided several historical accounts for many of the atrocities committed against women, and varying traditions which certainly seemed to offer more enlightenment than our own. After remarking that abstinence only education was “the only course [she had] ever seen that rewards you for ignorance,” she went on to discuss a very forward-thinking system—located decidedly in the past.

In particular, she explained the traditions of many of the indigenous people of the United States. She discussed their structure as being matralinear—in that women and men were seen as equals, and that, even when women were not chiefs, they were able to help choose their chiefs, and to remove them if necessary, by consent. Many did not even have the capability to speak about gender in their language. Yes, in many traditions women were concentrated in agriculture and men in hunting, but there was a happy fluidity between the two, and in many cases women and men alike were welcome to choose whichever they believed fit them appropriately. In fact, many that fell under what might now be known as the LGBT umbrella—particularly those of a trans* nature, to be anachronistic—were considered “twin-spirited,” and thus to have a broader knowledge about the world around them. They were frequently offered special privileges, like that of naming.

Of course, this was then followed up with a mention of the horrors that had been committed against them—one of which was that by the 1970s, a full seventy percent of Native American women had been sterilized—and our government had the nerve to explain this by claiming they would not know how to use contraception, though they had been using nature to produce their own contraception—and, in fact, to teach migrant women how to use contraception of their own—for hundreds of years.

By providing historical facts from traditions of both present and past, she was able to offer some insight into the immediacy and importance of the feminist struggle, and also the continued fact of its revolutionary aspect—because, yes, it is still very much a revolution. “When happens to women is culture,” she reminded us, by referencing a particularly notable quote. “What happens to men is politics.” She discussed the fact that the most reliable predictor of a country’s tendency toward violence is whether the country is violent with its own women, and she informed the audience that the number of women killed by their male significant others since 9/11 is larger than the number of people killed in 9/11 and people killed in the Afghan war combined. That is remarkable. That should be terrifying.

It was not the first terrifying fact she gave us, nor was it the last—but it was a stark reminder that there is a “war” that is far from won, one which she has seen raging for much of her life—one which she has existed at the helm for much of her life. And it is a crucial one—and it is difficult not to believe someone with the weight of presence and experience that comes with Gloria Steinem. One of the first comments she made in her speech was with regard, in fact, to the movement at large—and its relationship with other movements. In response to the critiques, she declared that it was not just an upper-class, white female movement—and that she was disgusted with the way the media had phrased all discussion surrounded the 2008 presidential election, as questioning whether sex or race was “more important.” She said, instead, “I hope we can begin to understand that our movements are linked, not ranked.”

The truth is, I don’t think that undoes some of the problems that have come with parts of the feminist movement. There have certainly been exclusionary practices in its history, and to heighten the problems of female-ness without regard to intersection, or to the weight of other oppressions, is absurd. But I hope that she is right, more than anything: I hope that we are moving toward a feminist movement that not only welcomes the experiences of everyone, but understand the nuances—the differences—in these experiences, an din these backgrounds, just as I hope we are moving toward equality, and toward a world where reproductive freedom is something that no longer needs discussion.

Near the end—before she answered questions, of which there were many—she commented on the fact that she had wanted a presidential debate that targeted a female audience, and focused heavily on what she called “women’s issues.” After a pause, she added, “I hesitate to say that, because—I know that we know what we mean, but there will always be that one reporter who will ask, ‘don’t you care about anything besides women’s issues?’”

She looked out to the audience and sighed, having spent part of her lecture already discussing the importance of a variety of matters outside what is generally lauded as “women’s rights.” And then she said, as she would say to the reporter, “Tell me one thing that would not be transformed if we looked at it as if everybody mattered.”

That, I think, might just be the kind of feminist movement I can believe in.