Photo by Fred Murphy/Creative Commons

Though election season this year, as ever, focused largely on the question of the presidency, it was in the matter of Congress that America bore witness to several surprising and heartening changes. Among these are several breakthroughs, including: Hiron’s election to Senate as the first Asian woman, Duckworth’s as the first disabled woman, Baldwin’s as the first lesbian, Gabbard’s as the first practicing Hindu, and Gonzalez’s as the first pansexual senator. These selections are absolutely cause for celebration; they are signs that are moving forward into more and more progressive times, whatever more conservative opponents might claim. One by one, we are changing the face of our Congress to one that reflects the actual composition of the country, which is, shockingly, populated by more than just aging white men. In fact, this is the largest coalition of female Senators ever elected to Congress.

There are certain questions to be asked, of course: for example, in some recent news articles regarding to female progress, no mention is made at all to the groundbreaking nature of the first pansexual Senator. Why isn’t this worthy of mention everywhere, like the others? It is likely due to the lack of awareness of pansexuality at large; an overwhelming number of people still are not aware what this means, and perhaps this makes it that much easier to brush aside. But that’s just the point: for a woman to identify in a way largely considered “unconventional,” and to be willing to engage in this identification with the world, is an absolutely staggering step to take. It will require a multitude of explanations, and it will require facing down waves of ignorance, but the fact that it might offer a greater number of people access to a lesser-known identity is certainly a step of which I am very grateful.

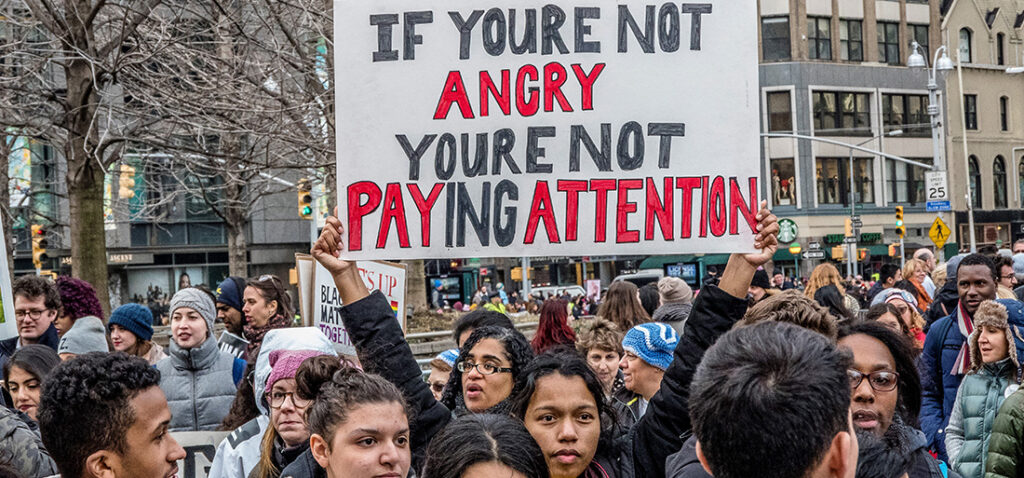

But I think it is important to note that these are the reasons—the election of so many women from relatively diverse background—to which people will point when they say “feminism is irrelevant.” There are more women in the Senate than ever before. Women are involved in government, in positions of power. And these are exactly the kinds of questions people kept asking after Obama was elected in 2008: are we a post-racist society? Does this mean we should no longer concern ourselves with the issues of racism?

No, we are nowhere near a post-racist society, and no, feminism is not irrelevant. Feminism may have been cast aside, and it may need to be rethought, and there is more headway than ever in our history—but it is far from irrelevant. Because racism and sexism work do not exclude particularly individuals from making headway in society, particularly at present. Racism and sexism do not bar exceptions; in fact, exceptions are crucial in the very foundation of both. “We have a black man as president,” someone might argue, as certain proof that there cannot possibly be any more limitations, if a man of color was elected to the most powerful position in the country. If one black man can do it, why couldn’t anyone?

That is not how racism works. That is not how sexism works. Exceptions do not discount privilege. Exceptions do not undo the foundations of our society that keep the minority from claiming identical spaces to the majority. We live in a society that still exhibits institutional privilege; that still creates separate standards on the basis of race and gender; that still revolves around a very white-centric perspective, whoever is in charge of the country. It is not he who dictates cultural consciousness, and it is not he who is able to rescind a history of perpetual discrimination.

Similarly, it is incredible that so many women have been able to achieve such an important grab for power in this last election. It is important headway. But it does not undo the institutions of privilege themselves, and electing a woman to serve at the top of a hierarchical pyramid does not undo the patriarchal elements that have created this system. As Gloria Steinem said, “Women entering into systems of patriarchy does not mean all women are empowered.” It is the system itself, and not a single individual, which continues to demand privilege for the majority who benefits from it—a majority intent upon maintaining its existence.

But they are not the majority in numbers. And though dismantling a system that has existed for centuries cannot be done with a single vote, or a single individual, it is nevertheless an important undertaking. Maybe it is time our democracy came without limits.