You know what’s always stressed me out? Back in high school, when we had to take standardized tests, there’d always be a preface question about which race you identify as. They’d list the options — African American, Caucasian, Asian, Latino, etc — and while most kids bubbled in their answer in about half a second, I always hesitated, trying to decide which category I fell under. My mom is definitely Caucasian, born and raised in Palatine, Illinois, a small suburb outside of Chicago. My dad, the son of two Romanian immigrants who settled in Queens, New York, is also definitely Caucasian.

But what about me?

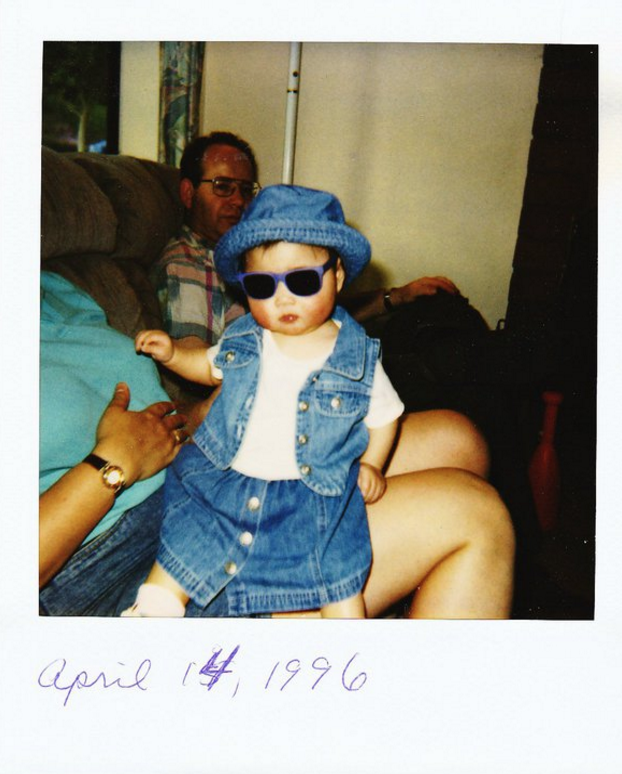

When I was nine months old, I was adopted from an orphanage in Sanshui, China and settled down in San Marino, California, a small town near the San Gabriel Valley. As the town with the ninth largest Asian population in the country, San Marino should be the perfect place for me to “reconnect with my roots,” but if anything, it pushed me further into confusion.

When I was nine months old, I was adopted from an orphanage in Sanshui, China and settled down in San Marino, California, a small town near the San Gabriel Valley. As the town with the ninth largest Asian population in the country, San Marino should be the perfect place for me to “reconnect with my roots,” but if anything, it pushed me further into confusion.

This is not to say that I didn’t like growing up in a heavily-Asian community — I loved being able to get literally any type of Asian food within a 15 minute drive from home, or going to 99 Ranch Market, perusing the aisles of brightly packaged snacks and perfectly marbled meats for shabu shabu. It’s more that I felt uncomfortable; I identified with the Asian community purely based on appearance, but culturally? Not in a way that felt valid. Instead, I culturally identified as “Classically American,” whatever the fuck that means — another grey area I guess. Plus, I was raised in a traditionally Jewish household, bat-mitzvah and everything, so being the only Asian person at my temple put an even deeper wrench in my own cultural identification.

A Jewish Sort-of-Asian-Sort-of-Caucasian-American girl. Potentially the only one on this goddamn earth. Yep. Definitely not on the STAR test bubble options. I settled with filling in the bubble next to Other.

I suppose “other” is the most accurate depiction of my cultural and racial identity. However, labeling myself as “other” just made me feel lonely and unrelatable. I felt like an outsider looking in on various identities that were never truly mine, no matter how welcoming each community was toward me.

And so my obsession with finding other groups with whom I identified began.

I guess I’ve always had a fixation with categorization. Maybe I can blame that on my Virgo sun’s need for organization, but regardless of whether it was caused by the stars’ alignment at the time of my birth, it’s an obsession nonetheless. I joined the marching band when I entered high school, and embraced the camaraderie of my fellow trumpets in the section. I identified as a trumpet player — loud, egotistical, definitely annoying — and although these traits may not be the most positive, the sheer sense of belonging among other loud, egotistical, annoying people was enough to keep me sucking down the marching band kool aid.

I guess I’ve always had a fixation with categorization. Maybe I can blame that on my Virgo sun’s need for organization, but regardless of whether it was caused by the stars’ alignment at the time of my birth, it’s an obsession nonetheless. I joined the marching band when I entered high school, and embraced the camaraderie of my fellow trumpets in the section. I identified as a trumpet player — loud, egotistical, definitely annoying — and although these traits may not be the most positive, the sheer sense of belonging among other loud, egotistical, annoying people was enough to keep me sucking down the marching band kool aid.

It wasn’t until college that I even thought about my place in the queer community. Up until halfway through my freshman year, I hadn’t even considered the possibility of being gay.

Unlike many of my friends back in middle school and high school, who spent the days fawning over their crushes, I had never really placed a priority on romance. I blamed it on the fact that all the boys at my school were gross and uninteresting and that I didn’t want to waste my time on them when I could just wait for The One, who’d probably be found elsewhere. I thought I was just being Reasonable and Mature For A Teenager, because in the grand scheme of the rest of my life, the chance I’d meet The One before even going off to college seemed highly unlikely.

Even the few crushes I did have during that time seemed stereotypical, or heavily influenced by my friends. In middle school I “fell” for the literal boy-next-door, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed boy who always invited me over to play with his legos. In high school, I dated a boy who I met in band, who I hadn’t even considered until all my friends started talking about how cute he was, and how lucky I was to have a class with him.

But when I came to UCLA, all the pieces, the hints that were SO STARKLY OBVIOUS that I had ignored, came to light. That high school best friend who I thought I was just reeeeaaaaalllly close with? Definitely in love. Definitely without a doubt so in love with her. Ooops. Now THAT’S what those butterflies and warm fuzzy feelings my friends had been talking about were.

Growing up in the San Marino bubble definitely distorted my view towards the world, as I was generally surrounded by privileged members of the upper-class who thrived on conformity and maintaining an “image of prestige.” In San Marino, I felt that I was better off repressing the areas of my life that didn’t match with what that society deemed as “normal” instead of expressing it, or even talking to others about it. Fortunately, coming to college and being exposed to so many different people with different perspectives and walks of life helped me realize how broad of a term “normal” is, and how it doesn’t require conforming to such rigid concepts, as I had faced in my hometown.

Growing up in the San Marino bubble definitely distorted my view towards the world, as I was generally surrounded by privileged members of the upper-class who thrived on conformity and maintaining an “image of prestige.” In San Marino, I felt that I was better off repressing the areas of my life that didn’t match with what that society deemed as “normal” instead of expressing it, or even talking to others about it. Fortunately, coming to college and being exposed to so many different people with different perspectives and walks of life helped me realize how broad of a term “normal” is, and how it doesn’t require conforming to such rigid concepts, as I had faced in my hometown.

Although I became aware of my queer identity during my freshman year, it wasn’t until sophomore year that I felt secure enough in my identity to start coming out. I remember being in Big Bear on a trip with a couple of my closest friends during Fall Quarter and finally pulling my friend (who quickly became my Lesbian Spirit Guide) aside and telling her that I was gay, to which she immediately responded with “welcome to the fambly” with a big smile. And that’s when I knew that this community, the queer community, was one that I’d be comfortable in — one in which I could truly identify.

Although I became aware of my queer identity during my freshman year, it wasn’t until sophomore year that I felt secure enough in my identity to start coming out. I remember being in Big Bear on a trip with a couple of my closest friends during Fall Quarter and finally pulling my friend (who quickly became my Lesbian Spirit Guide) aside and telling her that I was gay, to which she immediately responded with “welcome to the fambly” with a big smile. And that’s when I knew that this community, the queer community, was one that I’d be comfortable in — one in which I could truly identify.

To some degree, I think that my entrance into the queer community, and with it, my exploration deeper into the concept of identity, helped me come to terms with my confusion about cultural and racial identity. Meeting people who literally identify as non-binary or on the gray-sexuality spectrum really helped me realize the true validity of an ambiguous identity, which is ultimately where I identify, racially and culturally.

—

With adoption, not everyone’s story is like mine — each adoptee has their own story. Even adoptees raised in families with multiple adopted siblings process their experience differently, because every little detail can cause big changes in perception.

I was fortunate enough to talk to two other queer people of color (QPOC) adoptees about their individual experiences with adoption and the queer community.

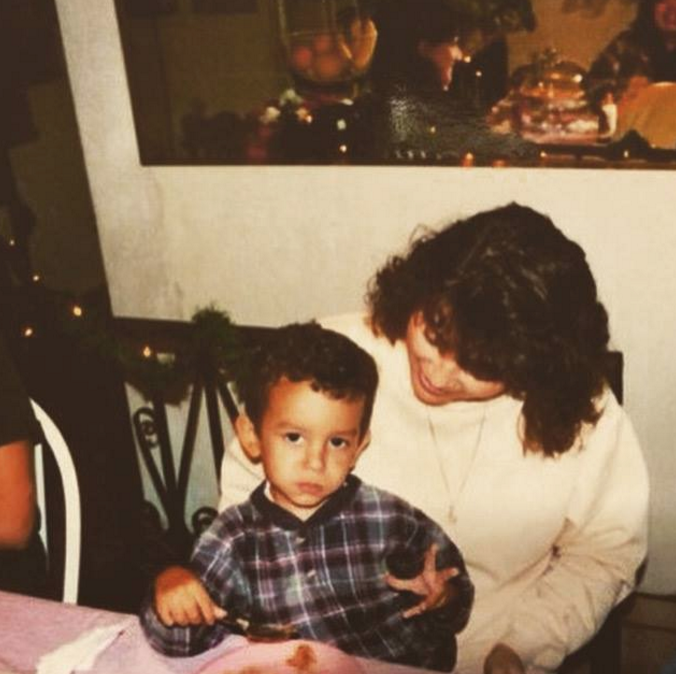

Zoe Dunne is a 4th-year student at Western Oregon University whom I’ve known longer than most other humans on this earth — even my own parents. Zoe and I were adopted from the same orphanage in Sanshui through an adoption agency that allowed our parents, along with about 20 other prospective parents, to experience the adoption process as a group. Our families traveled together to China, spending half of the week-long trip getting properly prepared (and panicked) for parenthood, and the other half, after having visited the orphanage and picking up the kids, actually doing the parenting (and probably still panicking).

Whereas I grew up as an only-child, Zoe grew up in a fairly large family. At the time of her adoption, Zoe grew up with a Caucasian single mother and 4 siblings, all birth children of her mother, in Malibu. She notes on her own identity issues: “Definitely when I was young I went through an identity crisis because at least for me, I’ve always known I was adopted, but then [I’ve grown] up in this white culture and I lived in Malibu, so mainly everyone’s white, but I’m not white.”

Whereas I grew up as an only-child, Zoe grew up in a fairly large family. At the time of her adoption, Zoe grew up with a Caucasian single mother and 4 siblings, all birth children of her mother, in Malibu. She notes on her own identity issues: “Definitely when I was young I went through an identity crisis because at least for me, I’ve always known I was adopted, but then [I’ve grown] up in this white culture and I lived in Malibu, so mainly everyone’s white, but I’m not white.”

For Zoe, the main point when she started noticing the racial discrepancy between herself and her parents came when people started asking questions regarding that discrepancy. She said that people would even say things like “I’m so sorry,” in response to her explaining her adoption background. Zoe states, “You try not letting that stuff get to you, but it kind of does because I am really different.”

The summer after high school, Zoe and her family, along with a therapist, took a trip back to China to reconnect with her roots. There, she was asked which place she views as “home” — China or America. However, she was unable to come to a conclusive answer, despite thinking about it very deeply. She says that “in a way, I don’t identify really as Chinese, other than feature-wise, and I’m not white either, so it was really confusing.”

In a way, adoption and confusion come hand-in-hand. As adoptees, we are constantly faced with questions ranging from simple biological questions (eg: Am I deathly allergic to bees or were those hives just a coincidence?) to more complex questions regarding identity and “home,” to which we simply don’t have the answers.

Similarly to myself, Zoe found a lot of answers to her questions, or at least relief from the confusion of identity, when she came to college.

Zoe feels that her identity in the queer community was never a huge issue, as she didn’t face strong issues with either self-acceptance of her queer identity or public-acceptance when she came out. She’s grateful that in college she can surround herself with friends, both queer and non-queer, and that she can depend on them when struggling in certain areas of her life that she feels uncomfortable discussing with her family. As someone who identifies as pansexual, she enjoys “support from both the queer and non-queer communities to validate both her queer and heterosexual feelings.

Zoe feels that her identity in the queer community was never a huge issue, as she didn’t face strong issues with either self-acceptance of her queer identity or public-acceptance when she came out. She’s grateful that in college she can surround herself with friends, both queer and non-queer, and that she can depend on them when struggling in certain areas of her life that she feels uncomfortable discussing with her family. As someone who identifies as pansexual, she enjoys “support from both the queer and non-queer communities to validate both her queer and heterosexual feelings.

In the end, what allows her to find peace is the realization that cultural and racial identity doesn’t need to be constrained to the divisions that society tries to organize everyone into. She states, “I was able to come to the conclusion that to me, I’m my own home. I don’t have to fit into any racial group or cultural group — it’s just me and that’s who I am.”

—

Jeremy Porr is a student at SFSU studying Journalism, with a minor in Race and Resistance. Jeremy’s adoption story is much different from that of mine and Zoe’s. Jeremy was adopted at 5 or 6 months by a Latino family and “seamlessly blended in” due to his similar complexion and “racially ambiguous features.” It wasn’t until college, where he started taking courses that made him think about race in culture in a more critical way, that he started questioning his own racial identity.

Growing up, he always knew he was adopted, as his parents were very open about the process. However, in the past few years, he started posing deeper questions about the adoption, wondering what his race is according to his birth lineage. When an ancestry test based on his mitochondrial data didn’t provide the closure he needed, he turned to his adoption papers for further answers. He found out that he actually had three other siblings, and that his birth mother had expressed interest in keeping in contact with him, which he hadn’t known about before, leaving him with more questions than answers.

Growing up, he always knew he was adopted, as his parents were very open about the process. However, in the past few years, he started posing deeper questions about the adoption, wondering what his race is according to his birth lineage. When an ancestry test based on his mitochondrial data didn’t provide the closure he needed, he turned to his adoption papers for further answers. He found out that he actually had three other siblings, and that his birth mother had expressed interest in keeping in contact with him, which he hadn’t known about before, leaving him with more questions than answers.

At this point in his life, Jeremy’s attention is mainly dedicated to graduating from college, which I definitely relate to, but all the questions that come with his own background and lack of knowledge are still present on his mind.

With regards to identity, Jeremy feels that being a QPOC adoptee “has stressed the importance of chosen family … I think the entire concept of family is queer, because yes, I have my parents who I love, but we’re not related by blood, and that doesn’t matter to me.”

—

Although everyone’s story and experiences are very different when it comes to adoption and queer identity, there is certainly a degree of intersectionality between the two communities. In the end, the QPOC community and adoptee community are both minorities who are very rarely represented in day-to-day life, and often if they are represented, their situations are romanticized. Adoptees are often seen as “tragic figures,” who spend their days wallowing in self-pity about never having known their “real parents” (can confirm: not what we do). QPOC, if even presented in media, are usually branded with one Ultimate Combo Stereotype that fetishizes both their race and their sexual identification.

I know that growing up, I had a hard time coming to terms with my transracial adoption because I’d constantly be bombarded with questions about my background that I didn’t have the answers to, and on top of that, I didn’t really have figures to look up to who had shared that same experience as myself. I still can barely name any famous adopted people, let alone ones who are vocal about their experience as an adoptee.

Zoe felt similarly about this experience, specifically dealing with adoption questions at a young age, stating, “No one else is adopted so we’re like NO ONE ELSE GETS IT! … It was definitely a big insecurity of mine, and I went to therapy, but [I was] pretty young so it [was] confusing.”

Jeremy also discussed the importance of being vocal, as an adoptee.

“I think that’s another thing that gets lost. Birth parents have a much louder voice than the adoptees do within the adoptee community. The narrative and feelings of the birth parents are placed at a higher priority than the adoptees, which also affects our psyche because as we get older and have these questions, we’re told that we should be grateful. On the one hand that’s great, but also adoption is a trauma for children to go through that we don’t have a choice in … It’s not a one-time event, it’s a lifelong process … and it’s important for our voices to be heard.”

This need for awareness — this need for vocality — is so important in the QPOC community as well. While I was talking with Jeremy, he brought up the fact that he never really felt comfortable or welcomed by the LGBT community, because when he was coming out, the faces that represented them were mostly white, homonormative, and cis-gendered, which is not a community to which he related.

“In terms of the mainstream LGBT movement, I think they’re still focused on things like marriage and adoption rights, and that’s great, but also what about homeless queer youth? What about trans women of color who are murdered at an insane rate? … Especially in this Trump era, I want to be more queer and more in people’s faces than ever before. If I want to wear eyeliner and tights and go out, that’s what I’m going to do. I have no interest in watering down my queer identity to become some homonormative clone to please straight people.”

“In terms of the mainstream LGBT movement, I think they’re still focused on things like marriage and adoption rights, and that’s great, but also what about homeless queer youth? What about trans women of color who are murdered at an insane rate? … Especially in this Trump era, I want to be more queer and more in people’s faces than ever before. If I want to wear eyeliner and tights and go out, that’s what I’m going to do. I have no interest in watering down my queer identity to become some homonormative clone to please straight people.”

As of now, I’m still a little unsure of my own racial and cultural identity — what’s changed is my own acceptance of that gray-area as a valid identity. I guess in the end, the biggest thing standing in the way of this realization was myself. Growing up, I was so afraid of judgment and how others would perceive me that I searched for possibilities of which identities I could fall into instead of focusing on being myself, but here at UCLA I’ve never felt more comfortable being myself: a Jewish-ish Sort-of-Asian-Sort-of-Caucasian-American Queer Person of Color.

However, I’m just one person and can’t speak for the rest of the world’s adoptees or QPOC. I live in sunny Southern California and attend a university full of other young, diverse liberals such as myself, so it’s no doubt that there are many, many others out there in different communities who do not have the privilege of feeling comfortable expressing themselves. At this current age under the Trump Presidency, it’s vital for people like myself to maintain an active voice for the communities that don’t have the luxury to do so. It’s our job to show the nation — to show the world — that we, these communities of “others,” whether we be racial minorities, queer people, adoptees, or all three, are here and demand to be respected for who we are.

This article was featured in OutWrite’s Winter 2017 Print Edition. Contact us at [email protected] if you’re interested in receiving a copy!

I would love to have you as a guest speaker with China’s Children International Pride!! Please reach out to me personally at [email protected]. I am part of a Chinese adoptee community made for and by adoptees. Here is more information:

http://chinaschildreninternational.org/

I am the current coordinator for the Chinese Children International Pride community – we are a minority in a minority from all walks of life, born from the same Chinese roots and identity on the LGBTQIA spectrum. Please consider and reach out to me if you are available and interested in joining our CCI family who currently live all around the world!