Artworks by Alex Donis

This article was last updated on 4/17/22 at 1:32pm.

Censorship of LGBTQ+ media throughout history and throughout the world is something that affects a lot of art and a lot of artists, a lot of people inside and outside of the community. Hearing about it is one thing, but to actually have your art destroyed and taken down, to have your art censored, would make it a completely different story.

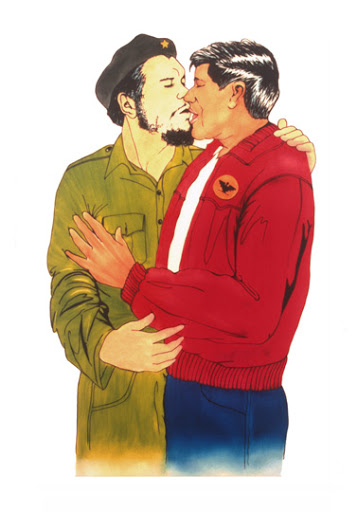

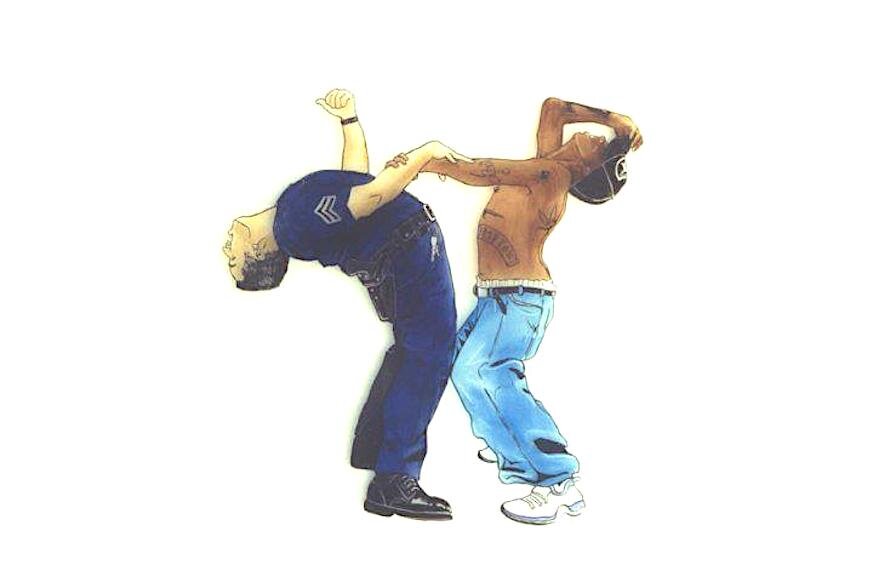

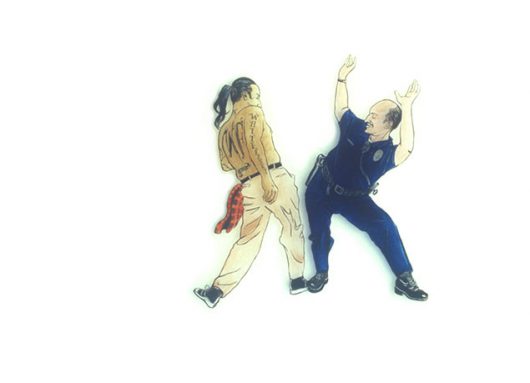

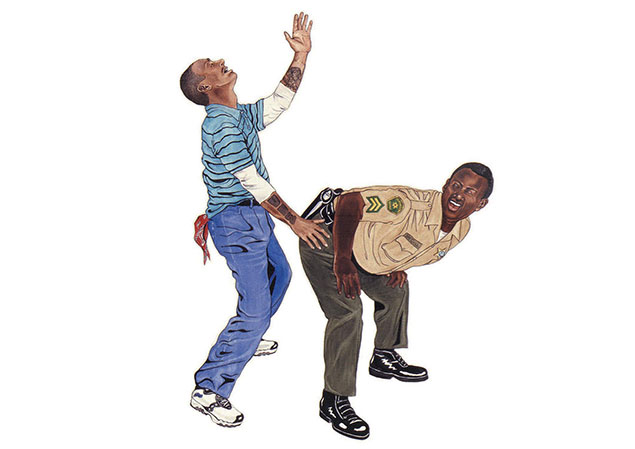

LA-based queer artist Alex Donis aimed to create art that was about queer love, about queer happiness, truly desiring to simply bring people together. Ironically, with this goal of love, his pieces faced nearly the opposite: they were taken down, harassed, smashed, destroyed; you name it, his pieces were subjected to it. What did his pieces include? Well, look for yourself:

Alex Donis, My Cathedral, 1997 (source)

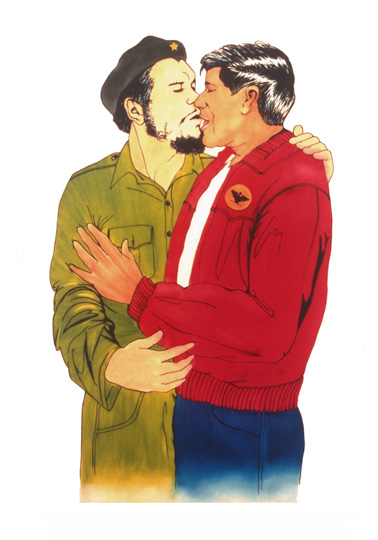

Here’s how it looked after it was destroyed at Galería de la Raza in San Francisco:

(source)

Shortly after placing the pieces at Galería de la Raza in San Francisco in 1997, they were destroyed. Donis recalls receiving the first call that they’d been vandalized, and then the second, lamenting that after finding out that the works had been destroyed, he felt a sense of disheartenment. “I felt very, very emotionally attached to the artwork,” Donis remarks.

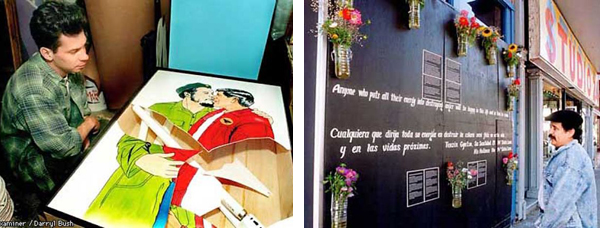

What do you do when somebody does this to your work? Do you stop making art? Or maybe stop showing it? Donis told me that this exhibit helped him learn to not be so attached to works in the future and made him aware that this treatment towards his pieces could potentially reoccur. It, of course, did indeed reoccur in 2001, although this time at a place a bit closer to home for Donis, a place where he had previously taught: The Watts Towers Arts Center in Los Angeles.

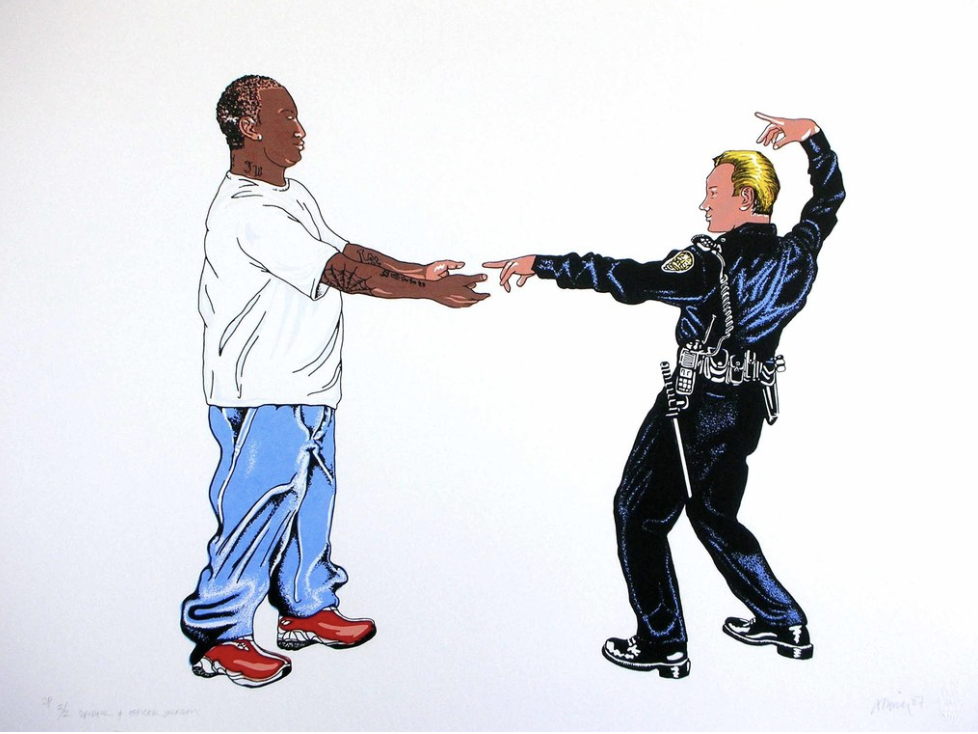

The history of poor responses towards his previous work affected what Donis would produce. “I was walking and feeling that I had already experienced something volatile, that I wanted to do something more tailored and less volatile. It would be about dancing, not something openly sexual, like a kiss.” The pieces that were to be displayed at the Watts Towers Center include the following:

(source)

(source)

(source)

(source)

Due to the tension between cops and community members during that time, a result of both the beating of Rodney King and the Rampart Scandal, Donis created these pieces to show an alternative to the brutality inflicted by the Los Angeles Police Department, that there could be a bit of levity to help counter the brutal reality of the war going on between LAPD and the community.

These pieces were met with threats of violence and protests from the community, and were eventually taken down before ever being formally exhibited to the public. Now, I wonder to myself, what’s so bad about two men dancing? What’s so bad about two men kissing, even if the men are Che Guevara and Cesar Chavez? What if the portrait had portrayed different men? What if, for either of the collections, the one with the men kissing, or the one with the men dancing, there had been a woman portrayed with the man instead? The issue within the destruction and censorship both these exhibits faced, as was noted by Donis himself, stems simply from one thing: homophobia.

The homosocial relationships presented in these pieces caused various groups and people to see what they believed shouldn’t be shown, that is, a relationship between two men that is civil and even happy. Donis comments that people saw this art as “pornographic.” I was curious as to how he was able to get past all this destruction, to which he comments that the one thing he thinks is important is to essentially be confident in his work and acknowledge the new life it takes on.

Donis recalls one particular example in Sheri Frumpkin, his art dealer. “Sheri was always like, … ‘Alex, somebody wants to sell these pieces, they’re doing an exhibition on the history of censorship, there’s a PhD candidate who’s writing an article on queerness in Latino art,’ it was nonstop.”

He also mentions the importance of having a Public Relations team, which he learned after the first incident that happened at the Galería.

“I remember just being very very emotionally attached to the artwork and feeling like ‘Oh my God I only got a chance to see that work maybe for a few months.’ You know, now it’s all swept up and thrown in a garbage bin,” Donis said.

The experience at the Galería San Francisco prompted Donis to put a larger focus on a PR team, hiring one for the first time for his next exhibit at The Watts Arts Center (the place that ended up not even showing his pieces for fear of the community’s reaction). He notes that this taught him a lot about “institutional censorship,” mentioning that the mayor and a city councilwoman both got involved in the fight to take down his art, putting “a lot of pressure on the department of cultural affairs and the director of the gallery” to prevent the pieces from being shown. He reflects on the difference between having a helpful gallery and Public Relations team in handling these situations, the difference between a gallery that wanted to sit down and talk with the community about the situation, and a gallery that took the art down when the community complained about it; he comments that a good Public Relations team was integral to fighting what had happened. The team he hired brought the incident to both Spanish and English news media, an act he views as responsible for getting the attention of the ACLU who publicly spoke up against the Arts Center and the people who had pressured them to bring down the pieces. Although this didn’t lead to the pieces being reinstalled in the gallery, it led to, as he remarks, the pieces gaining a new life with their newfound importance as an example of censorship of queer art.

Not even taking into account the way in which it was censored, Donis’s art also provides an example of queer love and love aloneshown in the pieces above,. The impact of queer art that depicts love on the queer community is equally powerful whether it has been censored or not. It shows young queer people that it is okay to be queer, that it is not only acceptable, it is celebrated. Censorship of such art creates questions as to why it is being censored, who is censoring it, and the reasoning behind it. It makes people think about the power structures behind this censorship, about the deeper reasons for a gallery to have a PR team (or not) for a queer artist who makes queer art. The censorship, for me, means that we must make more queer art, especially more queer art that depicts this love, this camaraderie, this romance.

If you are a queer artist and would like OutWrite to interview you about or showcase your art, send an email to [email protected] or send us a message on Instagram (@outwritenewsmag).

Credits:

Author: Kaitlyn Germann (She/Her)

Copy Editors: Angela S, Iliana Resendiz, Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)