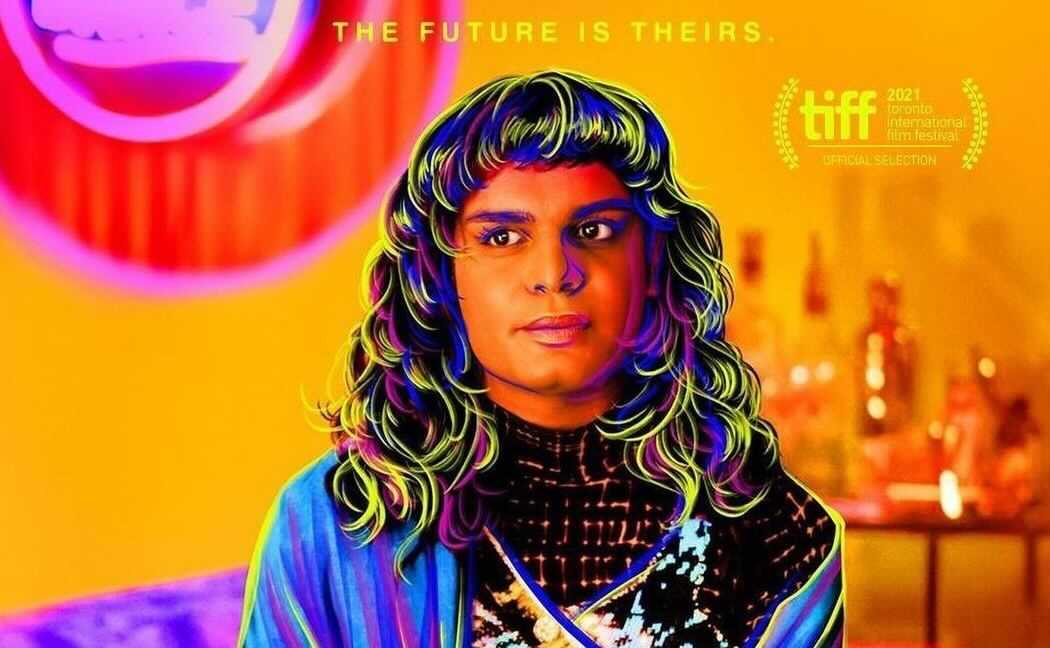

Still from HBO’s “Sort Of“

**This article contains minor spoilers for HBOMax’s “Sort Of”**

When I first saw the trailer for HBOMax’s “Sort Of” featuring Bilal Baig, — the first queer, South Asian, Muslim actor to lead a Canadian primetime television series — as the main character, Sabi, I was instantly filled with joy. I knew that regardless of the what, or the content this representation would give for many Queer South Asians, that the how, or the ways in which Sabi’s story was told, would be groundbreaking yet familiar all at the same time.

Sabi, a simultaneous bartender and nanny, is accompanied by their friend 7ven, played by Amanda Cordner, throughout the series. 7ven initially invites Sabi to Berlin, only to be turned down after the family Sabi cares for experiences a medical emergency, the mother hospitalized after a motorcycle crash. This happens quite early on in the season and sets up a salient theme for many South Asian youth. This idea of want versus need, obligation versus destination, is very impactful for Sabi’s story. They know their responsibility means they must stay and take care of the family they nanny for, even if they feel their heart calling them to Berlin. I think that’s a tale many South Asian folks know too well, particularly those of the diaspora: the clash between passion and the present. Responsibilities and reality are at odds with running away and chasing the future one so desperately wants.

But Sabi’s story also desperately warns us of the limits of what representation, particularly for South Asian folks, can often demarcate. It is easy for us to look at South Asia with a monolithic, problematic viewpoint. Edward Said, in his famous work, “Orientalism,” describes the way in which Western academics, intellectuals, and leaders portray and look to Asia as a commodifiable culture. I want to draw upon this idea and caution other South Asian folks, other queer South Asian folks too, from commodifying and painting a broad brush over Sabi’s story. There is no tale of “South Asian-ness” to find here. There are aspects of Sabi’s tale that we cannot all understand. They face the expectations of being in a Pakistani, Muslim family. Not all South Asians can understand that experience, but we can look to it to appreciate the diversity of experience within our diasporic communities.

There were a few particularly impactful moments in the first season that I wanted to share because they speak to why storytelling for our communities is so important. I think the series is worth watching in its entirety, so I won’t give it all away, but here are a few teasers.

I remember a particular moment when Sabi’s mom, Raffo, sees Sabi presenting as femme for the first time, with makeup and an outfit unapologetically them. This moment is so powerful because you get to see what Sabi’s mom is thinking without many words. She looks at them with bewilderment, misunderstanding, loss, and a sense of sadness. She does not understand the person in front of her, regardless of how much Sabi understands themself. This moment is so real for so many of us. It’s the first time our families, who have drawn up their conceptions about who and what we are, have their ideas about us destroyed by our own doings and intentionality. It was uncomfortable, raw, and beautiful all at the same time. I even found it amusing that Sabi’s mom was dropping off food for Sabi before the encounter in a typical motherly fashion.

When Sabi was not picking up their phone calls or answering their texts, the show quickly became an advert-esque onslaught of statistics about trans people of color and violence against them. This is an absolutely important conversation and the situational context of the story helped bring up important conversations about the violence this community faces. However, not only did this read as informative, but I thought Sabi’s processing of people looking for them was particularly impactful. A woman tells Sabi, as they are coming to terms with so many distraught people wondering where they are, “You must be really important.”

This is so powerful for so many of us queer folks, particularly queer people of color. We do not get the chance to feel important or feel like the center of our own stories. Sabi realizes they have a lot of people depending on them for joy, responsibilities, and much more. It is burdensome, but at the same time affirming. It’s why they chose not to leave for Berlin and why they look after the kids they babysit. That sense of interdependence speaks to the community and its ability to look after one another.

The pilot episode opens up with Sabi actually being let go by the family they nanny for before the devastating motorcycle accident leaves the family’s mother in the hospital and requires Sabi to stay. The father, Paul, who clearly has a complicated, unspoken, and uncomfortable relationship with Sabi, makes a comment that initially reads as microaggressive, acknowledging that “It may be hard for someone like you to get a job.”

While it is tempting to read this as the father alluding to Sabi’s transness, this situation goes deeper than the necessary conversation about queer folks experiencing discrimination in hiring and the workplace. It goes beyond that. When clarifying what he meant later, Paul says that he did not mean that it was Sabi’s identity that was going to hold them back from getting work. Rather, he clarifies, it was about Sabi being “so guarded.”

To be honest, it’s true. Throughout the series, particularly in the introduction, Sabi struggles to elaborate on their emotions. They fail to tell the mother who later gets into a crash that they’re going to miss them when they leave their nannying job, after being fired. They fail to follow up with their friend about whether leaving for Berlin is a possibility. So often, queer people’s trauma is used as a way to give them a sense of emotional maturity. There’s this conception that somehow we have lived through it all and we know best. That is equally dehumanizing as assuming the opposite. We have complex, at times immature, moments. Sabi is no different, and their lack of vulnerability, at times, is so necessary to humanize who they are and what “Sort Of” represents.

Credits:

Author: Shaanth Kodialam (They/Them)

Copy Editors: Brooke Borders (She/Her), Bella (She/They)