Graphic by Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

As we leave June’s LGBTQ+ Pride Month, we are welcomed by July’s Disability Pride Month. First celebrated in 1990 in Boston, Disability Pride is essentially a celebration of the bodies and minds we have. This month also acknowledges the landmark passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which was signed into law by former President George H. W. Bush on July 26th, 1990 with the purpose of prohibiting discrimination against people with disabilities. Over the past 32 years, many states and countries (source) have joined in having Disability Pride marches and events. Though not nationally recognized, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio declared July as Disability Pride Month in 2015.

Disability Pride, according to Ameridisability, “celebrate[s] ‘disability culture’ with the intention to positively influence the way people think about and/or define disability and to end the stigma of disability.” Disability takes on many forms, which includes, but is in no way limited to, physical disabilities, mental disabilities, neurological disabilities, speech disorders, sensory disorders (such as Deafness and blindness), and many more, making it even more important to create inclusive and open spaces for all disabled people, regardless of their specific condition, age, race, gender, or socioeconomic class. As a result, the disabled community is the largest minority group in the world with approximately 1 in 4 Americans living with a disability.

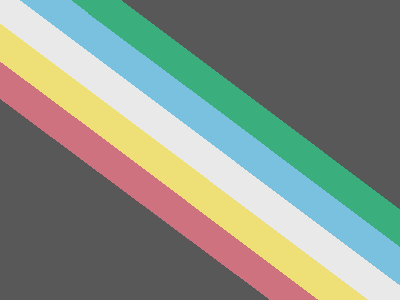

Just as LGBTQ+ communities have multiple representative flags, the most prominent of the Disability Pride flags is of a black rectangle with diagonal zigzag lines in the following colors: blue, yellow, white, red, and green. As Dr. Carlie Rhoads from the American Foundation for the Blind writes:

“The lines are considered to be a lightning bolt and each color represents something unique about the disability community. The flag was created to encompass all disabilities and was designed by Ann Magill, a member of the disability community. The black background represents the suffering of the disability community from violence and also serves as a color of rebellion and protest. The lightning bolt represents how individuals with disabilities must navigate barriers, and demonstrates their creativity in doing so. The five colors represent the variety of needs and experiences: Mental Illness, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Invisible and Undiagnosed Disabilities, Physical Disabilities, and Sensory Disabilities.”

(A picture of this flag can be found at the bottom of this article!)

More recently in 2021, creator of the flag, Ann Magill, came out with a Visually Safe Disability Flag. It came to their attention that “even with desaturated colors, the zigzag design can, when viewed online (especially while scrolling), create a strobe effect and pose a risk for people with epilepsy and migraine sufferers.” This revised flag is, therefore, more accessible to the community and an improved method of awareness for Disability and Disability Pride.

The visually-safe disability pride flag designed by Ann Magill.

Though the term Pride is mostly associated with the LGBTQ+ community, Disability Pride Month isn’t exclusively for Queer individuals. Rather, the word “pride” is used to honor, celebrate, and reclaim our disability visibility in public spaces, where we haven’t always been welcomed, nor allowed, similar to most LGBTQ+ individuals. In fact, disabled people used to be prohibited from appearing in public due to legislation dubbed “The Ugly Laws,” the last of which was repealed in Chicago in 1974.

The intersections between disability and queerness are very real, as so beautifully demonstrated in this infographic. Queerness and Disability live in a space with “the roughly shared goal of battling assumptions that the way we are is somehow pathological, and the emphasis on joyful visibility that emphasizes our difference, rather than hiding or obscuring it” (Forbes). This calls attention to the need for (Queer) Disability Pride to not only reclaim our space but also to celebrate the eternal beauty of our bodies and intersectional identities, regardless of what society deems “normal.”

Throughout this month, I will highlight a variety of disabled and queer artists, cultural workers, activists, creators, and overall engaging individuals. With this series, I hope to educate those inside and outside of the disabled community, provide resources for those in search of ways to help out, — especially in light of the political catastrophe America is in right now — and most importantly, bring a spotlight onto these wonderful human beings.

While researching for this series, I found this beautifully written essay by J. Logan Smilges, titled “Pride Feelings,” where they claim that,

“Pride is not just about how a person feels toward themself but also about how they feel toward others and how they imagine others feel toward themselves. Pride can only exist, it might be argued, if we believe someone else is feeling ashamed. This is certainly the colonial logic underpinning both LGBTQ Pride and, to an extent, Disability Pride: that our communities must show pride as a form of emotional resistance to the rest of the world’s shame. But what I’ve come to wonder is whether the compulsion to express pride, especially in light of its tethering to white ablenationalism, makes it more difficult for us to respect the complex emotional entanglements of gender, sexuality, and disability.”

As a neurodivergent person, I find myself struggling to deal with the language to express myself as well as my identities, and oftentimes invalidate myself and feelings. I want to feel the Pride of being neurodivergent, but when so many societal forces work against and constantly question my very own identities, I feel unable to accept myself; I am on the journey of unlearning my own internalized ableism, and I can only remain optimistic for myself and those around and affected by me.

There is so much to learn and say about Disability (and Queer) justice, history, and activism, and I cannot do it alone to its fullest integrity. So, below are some great articles and resources for this year’s Disability Pride:

11 Ways to Celebrate Disability Pride Month (2022) By Daphne Frias from Good Good Good

Everything You Need To Know About Disability Pride Month in 2022 By Jessica Ping-Wild

“Nothing About Us Without Us” — Mantra for a Movement By Eli A. Wolff and Dr. Mary Hums

It’s Time to Expand the Narrative About Queer and Disabled Communities By Helena Emmanuel and Catherine Yarovoi

Spotlighting Disability (For sources on Disability Pride History) From the Illinois State Board of Education

LGBTQ+ People with Disabilities From Respectability

Disability and LGBTQA+ Resource Guide From The University of Arizona

Disability Statistics in the US: Looking Beyond Figures for an Accessible and Inclusive Society By Carole Martinez

Disability in USA From Global Disability Rights Now!

The Los Angeles Disability Pride Parade, Festival and Fair takes place in October, which is L.A. County’s Disability Pride Month.

The original disability pride flag designed by Ann Magill.

Credits:

Author: Giulianna Vicente (She/Her)

Artist: Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

Copy Editors: Bella (She/They), Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)