Sarah Belew/OutWrite

With its history of LGBTQ+ leadership through its board and founders, the Museum of Neon Art (MONA) has been a safe and welcoming space for the LGBTQ+ community since its founding in 1981. One of its current leaders is Eric Lynxwiler (he/him), a UCLA alum and former OutWrite editor-in-chief who is MONA’s President of the Board of Trustees and former Neon Cruise Bus guide.

On Oct. 29, 2023, Lynxwiler spoke at MONA’s event Light in the Dark: Queer Narratives in Neon, where newly acquired neon pieces that belonged to iconic LGBTQ+ spots in LA were exhibited. LGBTQ+ community members and artists also spoke about their experiences with queer neon history around LA.

One of the newly acquired pieces includes Midtowne Spa’s sign from downtown LA. Operated by Marty Benson from 1972 to 2022, the spa served queer men through the AIDS crisis. Lynxwiler explained, “Marty Benson was one of the leaders who actually said: ‘No, I’m not shutting these doors. Instead, I’m going to pass out condoms and teach everybody about safe sex.’ And then instituted the opportunity to get STD testing.”

Lynxwiler wrote to the spa for years trying to acquire the sign for the museum. He finally acquired it this year before the owners disposed of it during closing. The sign, made from purple and yellow phosphor glass tubing and argon mercury gas, now has a permanent home at MONA.

The second piece of neon art collected and now on display at MONA is the Body Builders Gym sign from Silverlake. From 1978 to 2023, the gym served as a non-judgemental space for a diverse range of queer male patrons. The owner, Jackie Joniec, checked up on gym members throughout the years and provided discounted rates for those diagnosed with AIDS, addiction and other health problems. Joniec donated the sign to MONA after the Body Builders Gym closed down because of post-pandemic struggles.

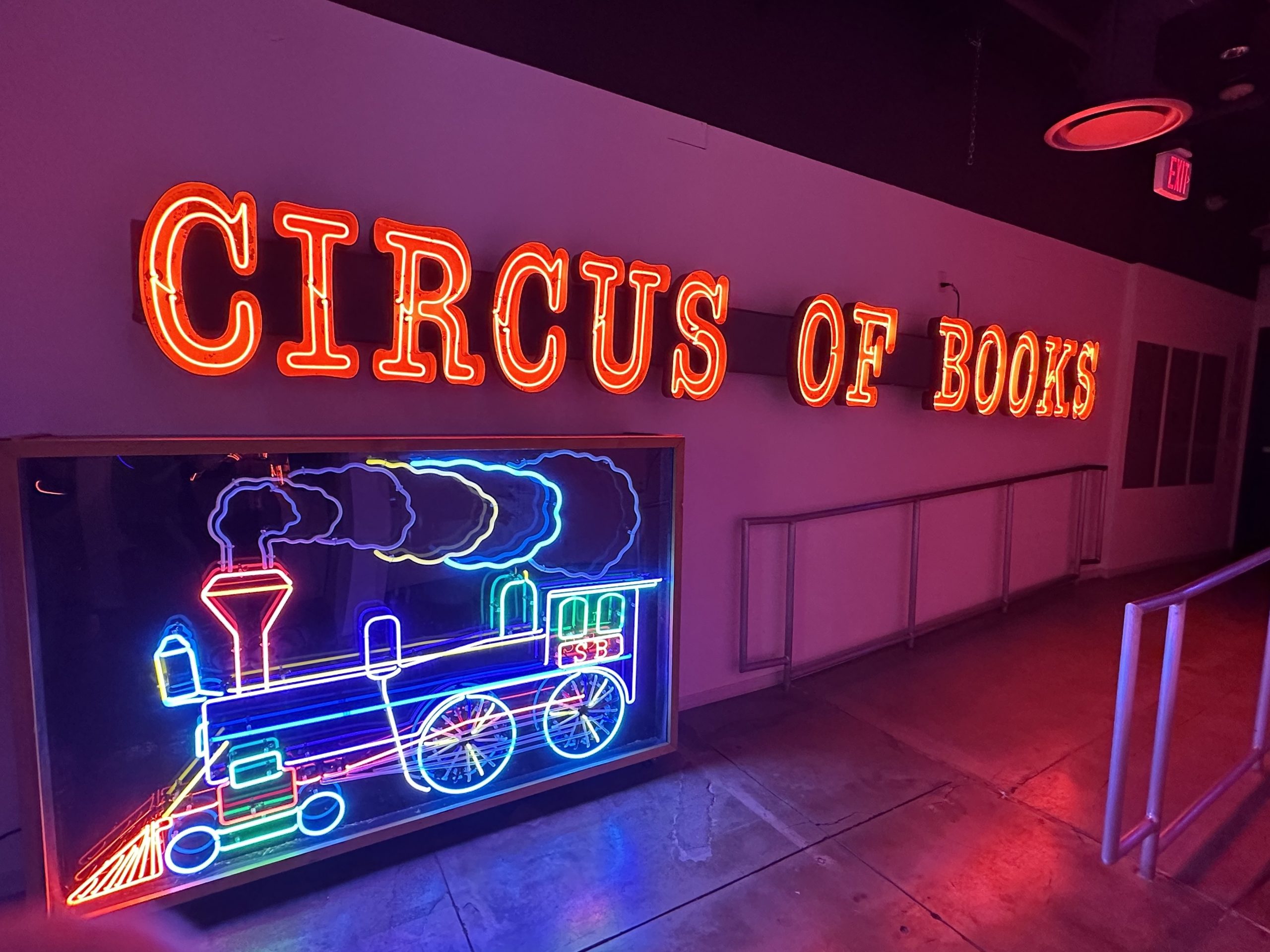

One of the crowning queer neon pieces is a sign from Circus of Books that has been at the museum since 2020. The store was a pornography bookshop until its original owner went bankrupt. Afterwards, Karen and Barry Mason bought the West Hollywood store in 1982 and turned it into a queer community icon. While the store operated, it provided a variety of straight and queer erotic books and videos to purchase. Circus of Books was a safe haven for the queer community in what was known as Vaseline Alley, a popular gay cruising spot.

Unfortunately, due to a shift towards finding pornography and erotica online, the original Circus of Books shut down in 2019. But its memory lives on in the Netflix documentary Circus of Books, directed and produced by the owner’s daughter, Rachel Mason.

At the MONA event, Mason talked about her experience growing up with the Circus of Books: “for anyone who doesn’t know, it really was before the LGBTQIA times. It was really historic for gay men and gay women at the time. My whole understanding of what the store meant for a generation that was lost and was wiped out and was under siege throughout my childhood. When the store was closing, I realized I needed to make this film because of all the guys that I loved, who died, and who — the few that were still there — understood how important the store was.”

Besides the beautiful works of neon artwork themselves, I had the pleasure of talking to two queer neon artists who have worked with the museum over the years. The first was Tyler Kensek (he/him), an artist and glass educator at the Museum of Neon Art. The following interviews have been lightly edited for concision and clarity.

Sarah: What does Neon Art mean to you?

Tyler: One thing I really like about it is that a lot of the axioms [established principles] are fixed. And that to me is really exciting because while the axioms are fixed, the creativity I see so many artists work with is just infinite. I like working with those constraints of [when] you only have a set number of colors you can choose from, a set number of gasses, kind of figuring out what you’ll do kind of within those limits. It’s really exciting to me.

Sarah: How would you say your neon art interacts with the LGBTQ+ community and how it’s influenced your work?

Tyler: When I first came to LA, I used neon to find my creative family. And there’s probably an analogy there with people finding their queer family. I find there’s, at least in my immediate community, it’s a community of really big exchanges of knowledge. Someone from Seattle will come to MONA, and I’ll pick up a skill from them, and then I can give it to someone that I meet from Hong Kong that comes in, and they’ll trade me that for something else.

The second artist I had a chance to talk to was Dani Bonnet (she/her), whose Cover Up, Cowboy neon piece is on display at the museum. Designed by artist Lauren Griffin (she/any) and bent by Bonnet, the neon cowboy switches between having his bandana on and off his face as a response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Sarah: How has your queerness and the LGBTQ+ community interacted with your art throughout the years?

Dani: I feel like I’ve been able to operate in a cool niche where I started off basically making signs for my friends because they’re the ones who are gonna ask you, like, “Oh, you do neon? Can I have a sign for my room?” So some of the first signs I made were for my queer friends ’cause you know how the community is, we’re all together. So one of my friends who’s a bit promiscuous, her name is Mary, and [the piece I made for her] was a pair of legs, [with] an open sign in the middle. So it was super iconic. And it really represented her. The name of the piece is Fuck Mary, Kill Me.

That was one of the first pieces that I’m proud of that I ended up making. It was like a celebration of free sex, you know? And then I really fell in love with making female legs, so, I would make a pair of legs, and then they would be sticking out of different places. And then, one of my gay friends, his name is Caleb, he’s like, “I love this, but can you make it gay?” And I was like,“Well, how could I make legs gay?” Like, what a challenge! So I countered him, I was like, “What if I did a boy butt? Would you be okay with that? Like a strong muscled butt.” He’s like, “I love it!” So also one of the first pieces I made was a nice juicy butt of a guy.

And then one of my first series that I did when I was first experimenting was Sad Fruit. Which on the surface is not very queer or gay, but each one of them was a representation of an ex that I had and how I associated the fruit with their personality and how that relationship was. So, that was a really fun series. The first one was a sad banana because on the dating profile of my ex, her picture was her eating a banana and I thought she was just like so badass. I love this girl, serious face, just chomping on a banana. So she’s a sad banana. And then I dated somebody named Danny. My name is Dani, so, you know, [it’s] like “Call Me by Your Name.” So I made her the sad peach.

But yeah, [my queerness] has always been there. And now I feel like that was just to learn. Now I feel like I’m starting to explore some bigger concepts. As an artist you should be able to explore and go where it’s taking you. So right now it’s been anti-capitalism for me. But even now, I still am queer, so it always is a part of that.

Although the Museum of Neon Art may be a small piece of the Los Angeles area art scene, it can be a light in the dark for many. In a time where so many queer spaces are moving online, MONA is a small queer refuge in the heart of a busy city that works to maintain the legacy of queer spaces that came before it. In an interview, MONA Executive Director Corrie Siegel (she/her) explained how neon and art is “just not like a white, cis, heteronormative product. It has bled into every different aspect of LA. There’s so many different groups of people in LA and neon represents that. […] With this collection, you really get to see how so many different communities contributed to what we see as the United States today.”

Credits:

Author: Sarah Belew (She/They)

Photographer: Sarah Belew (She/They)

Copy Editor: JQ Shearin (They/Them)