Illustrated by Steph Liu (She/Her)

This article was originally published in our Winter 2022 Volume 1 zine “Queer Rage, Resistance, & Renaissance.“

Personally, middle school is neither a place nor a period of my life I ever need to revisit, but since I have a younger sister in middle school, I’ve had to go back to the school grounds for events and rediscover the hellscape of my youth.

I am always struck by how much can change in six years. They repainted everything a slightly different shade. They added a whole new building and replaced the crusty water fountains with new shiny ones, and the arc of the water goes way higher than the sad dribble from my middle school days.

And, perhaps the weirdest change of all: they’ve started putting up posters affirming the identities of their queer students, and I feel incredibly weird about it for reasons I feel uneasy thinking about.

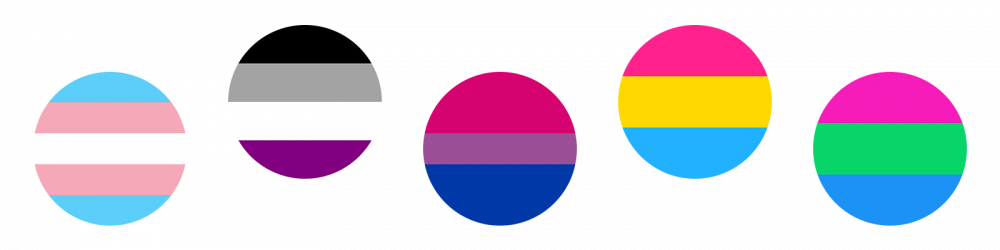

To clarify, these posters aren’t just the one-size-fits-all “Be nice to each other! Don’t be a bully!” flyers that were plastered around when I was 12. These posters have pride flags on them, and they say things like “Your identity is valid!” and “This is a safe space for LGBTQ+ students!”

There are other details I hear from my sister about what it’s like to be queer at her middle school now. She tells me about the high attendance of the school’s GSA club and that kids in her friend group can come out and talk about their identities openly and easily. Someone in her English class last year felt comfortable enough to joke about being gay in a class Jackbox game on the last day of school.

I almost can’t wrap my head around the enormity of change that has occurred in the last several years. Was it really only six years ago that I went to this school and felt locked in the closet with no key, knowing next to no one who shared my identity as a queer kid?

A large part of me is ecstatic about how far the school culture has come. Of course the place is not cured of queerphobia, but there is visible progress, and I can’t help but be excited for these kids.

The smaller part is less excited. A bit of it wants to shake the kids by their shoulders and tell them to hide. Another bit of it bares its teeth at progress. All the joy I feel when I look at the posters has a darker undertone of what first tastes like skepticism, then the sourness of scorn, then the bitterness of resentment. Why is this place which felt borderline hostile to me only six years ago somehow so friendly now? Why do these children have it so easy?

I am not proud of that part of me. I try to hush it up and paint over it. There is no reason for me to feel upset at progress, especially when I dedicated my time and energy into creating such a culture at my high school. I was a GSA club admin for three years. I represented the campus’s queer community during diversity events. It makes no sense for me to resent the kids of today having the freedom that I didn’t. But here we are.

I tend to cringe away from acknowledging my negativity, but if I poke a bit further at that writhing ball of bitterness and shine a bright enough light on it, I could see its stem—I could find out exactly what it is about queer middle schoolers openly being themselves that bothers me so much.

Here is the answer I discover: I have fallen into the easy trap of thinking that oppression defines the queer experience. I see one layer of oppression fall away, and my brain fixates on its absence. The bitter part of it sneers at the progress, saying, “Are you really queer if you didn’t have a shitty time in middle school?”

In other words, I am semi-consciously gatekeeping who is or is not “authentically queer.”

Unfortunately, gatekeeping within the queer community does not begin and end with my lowly simmering resentment towards openly queer pre-teens.

“I see one layer of oppression fall away, and my brain fixates on its absence. The bitter part of it sneers at the progress, saying, ‘Are you really queer if you didn’t have a shitty time in middle school?’”

For example, there is a faction of the transgender community called transmedicalists, or transmeds, who believe that a person must experience gender dysphoria and have a strong desire to medically transition in order to be legitimately transgender. Transmeds denounce individuals who claim the transgender identity without experincing dysphoria as “transtrenders,” or people who use the trans label to gain clout.

Although “dysphoria” could simply refer to an incongruence between a person’s assigned gender at birth and the gender they experience, it also commonly refers to the feelings of discomfort or distress that may accompany that incongruence. Thus, defining trans identity through dysphoria becomes tricky; how much discomfort or distress should a person experience and how visible does their dysphoria have to be before they are acceptably trans?

Another example of inter-community gatekeeping is acephobia, sometimes referred to as aphobia: prejudice against asexuals, people who experience little to no sexual attraction. Some argue that asexuality does not prompt the same oppression and violence as other sexual identities, and thus do not count as queer. Acephobic members of the community also argue that heteroromantic asexuals are “straight-passing” and do not deserve a space in the community.

“Straight-passing” arguments have also been used against bisexual, pansexual, and polysexual people in heterosexual relationships. These voices become especially loud during Pride month, when they police who should and should not come to events such as pride parades.

In their view, people in non-heterosexual relationships have a more legitimate claim over queer spaces because they are visibly, unquestionably queer. Meanwhile, the queerness of people in heterosexual couples are less immediately apparent, and they must verify their queer identities before they can be accepted into the space. But even then, straight-passing couples may still be subject to skepticism over whether they belong in a queer space.

The issue with gatekeeping is that it treats queerness as something that must be proven before it can be legitimate. But how does one prove that they are queer? Exclusionists point to oppression as a way to measure queerness.

But this measurement is problematic in itself; it emphasizes a pessimistic view that treats oppression as an inherent part of queer identity. This view burdens queer individuals with a standard of oppression when oppression is really a product of a queerphobic culture; there is nothing inevitable about queer suffering.

It costs nothing to be queer and costs even less to welcome others into the queer community. Exclusion and gatekeeping undercut the strength of the community and further marginalize the already marginalized.

How do we combat exclusionary forces in the community and in ourselves? My suggestion is that we should de-center suffering and re-center joy in our definitions of queerness. Rather than demanding that queer folks meet quotas of queerphobic experiences to justify their place in the community, community membership should be solely based on the individual’s relationship with their queer identity.

To the queer kids at my old middle school: I am sorry for my bitterness. It is not all I have—I promise, there’s much more I see when I look at you. I am proud of you. I am excited for you. I admire you. I will work to fight the part of me that clutches queerness to my chest like it’s something to hoard, and instead I will hold it out to you in open hands.

Credits:

Author: Steph Liu (She/Her)

Artist: Steph Liu (She/Her)

Copy Editors: Emma Blakely (They/She/He), Brooke Borders (She/They)