Photo by Christopher Ikonomou (Xe/He)

For a special edition of our Disability Pride Month Spotlight series, I was fortunate enough to interview our very own Editor-in-Chief, Christopher Ikonomou (xe/he). Xe is a fourth year student majoring in Communication and minoring in Disability Studies here at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Xe is active in university advocacy, such as with the Disabled Student Union and here at OutWrite!

During my time here at OutWrite, I have been motivated and inspired by Christopher to become part of the team and pursue writing at this newsmagazine. I was so excited to interview xem given that he has done so much in the past four years, like protesting with the Disabled Student Union and collaborating with CASETiFY on two different projects. Hearing how xe went from a middle school theater kid to our Editor-in-Chief was incredible, and I hope everyone enjoys reading this piece as much as I enjoyed talking to Christopher about it.

Disclaimer: This interview took place during Summer of 2022, and is now being published during October, which is L.A. County’s Disability Pride Month. For more information about October becoming L.A. County’s Disability Pride Month, look to https://www.disabilitypridela.com/ .

GV: If you could give our audience a quick little introduction to yourself, your pronouns, what you do, and anything else you want to share?

CI: Hello, my name is Christopher Ikonomou. I use xe/xem and he/him pronouns. As for labels, I’m a transgender, queer, disabled/chronically ill/visually impaired artist and activist, college student studying Communication and Disability Studies. My main thing outside of school, and even inside of school with working with OutWrite, is making artwork and speaking out about my intersecting communities of transness and disability with queerness sprinkled in there as well.

GV: Amazing. So right off the bat, you already said you claim the identities of artist and activist. So for you, what does activism look like?

CI: I think activism is a lot more multifaceted than a lot of people think; they think of fists up in the street marching with signs, you know, and they hate property damage and stuff like that. They basically think of a sanitized version of the civil rights movement when they think about activism; the only way to get something done through your marginalized community is to ask really, really nicely and by making really cool signs about it.

I think activism looks very different, especially for the disabled community, because a lot of us are literally excluded from physically protesting in the streets. For example, a lot of people on the [political] left and the right will criticize disabled people for not being in-person for protests, despite saying that masks are not required. [Disabled individuals] could be putting their lives at risk just for going and being with their community in-person. To me, activism for the disabled community, in particular, looks like whatever a disabled person can contribute toward their liberation. For some people, that looks like making TikTok videos that are creating awareness around their specific disability. For other people, it looks like getting a higher education and then using that higher education to create an online platform where they can tell people the nuances of disability and disability studies, educate a new generation of people about what it means to be disabled, and debunk a bunch of ableist myths that have been around for centuries.

For me, activism looks both like using my privilege as someone who’s not immunocompromised to get in the streets when I am able to. For example, at UCLA, I participated in a couple protests during the last school year, where in one of them, I slept in an administrative building for 16 days, mirroring what disabled activists like Judy Heumann from the 1970s did in order to pass Section 504 of what preceded the [Americans with Disabilities Act]. Activism is very complicated, and for the disabled community in particular, sometimes all you can literally do is what they call ‘keyboard activism’ — which I honestly hate that term, because it makes it sound silly, but so much awareness around disability happens online… [The COVID-19 pandemic] was kind of a breaking point of disabled people being like, “Hey, maybe our bodies are not disposable, and you should wear a mask and stay inside.” And that has come with a lot of ableist backlash on all sorts of social media platforms and has extended to other disability accommodations and stuff.

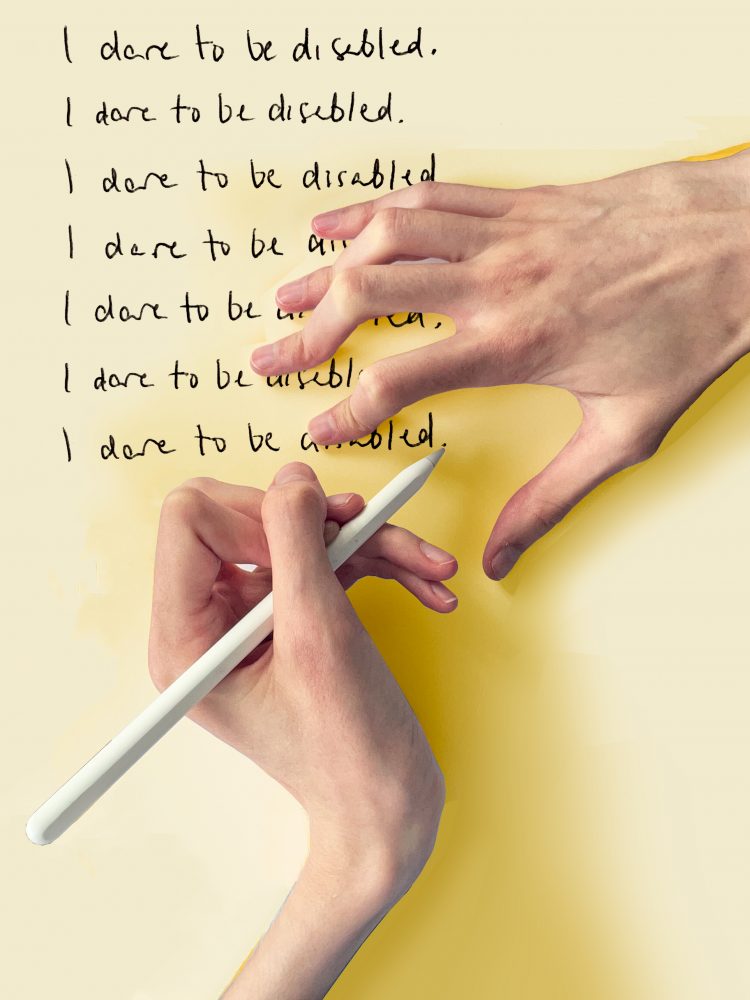

GV: Your art includes a lot of political stuff, too, which is, for me, a form of activism and advocacy. How do you use your art to advocate and be an activist? How did those two intertwine for you? How did you get into it?

CI: There’s this beautiful protest quote [by Toni Cade Bambara], that’s like, “The role of the artist is to make revolution irresistible.” The majority of my work is not overtly political (where it’s like saying specifically political message), but [for me] to exist in a queer and visibly disabled body is to exist as a political object. So everything, inherently, that I make is political.

My art and my videos really, at least recently, have been pushing more towards awareness of ableist microaggressions and how people perpetuate ableism in small ways that they may not realize. Literally two days ago, I went on a rant about how people don’t listen to visually impaired people and in 95% of the interactions I have, as a visually impaired person, people just list off like 10 of the same microaggressions every time, and people don’t realize that it’s wrong. So even just getting a comment that says, “Oh, I didn’t think about it like that,” is doing some sort of work for some sort of demographic that had never been exposed to that before.

It’s amazing to have a platform where younger people can look to me, instead of the ableism that they see in their everyday life, to learn how to treat disabled people. My art is pretty fun, and I have a little cute font, and I use a lot of colors and pride flags and stuff, but in the end, that approachability is what allows me to say a message that is tough to hear… Like the Supreme Court upheld that we can sterilize disabled people and it’s actually good for the country, or it’s a norm for myself to walk around in public and be the subject of staring for my entire life, even when I was a little kid. For those tough conversations, I think it’s a much more difficult pill for people to swallow that ableism is this horrific monster that a lot of people don’t realize is lurking under the surface in their everyday lives and even in government institutions. Putting makeup on the monster makes people feel a little more comfortable when talking about it.

GV: Thank you for sharing. When did you start getting into art?

CI: In general, my family is fairly creative. I’ve always been surrounded by artwork… One thing about my condition, Marfan syndrome (which I realized I forgot to mention in my introduction, but that’s an important part of my disabled identity), is that I was diagnosed when I was a really little kid, so my family was able to create my lifestyle around the restrictions that exist because I have Marfan syndrome. One of those restrictions is that you’re not allowed to do a lot of physical stuff like contact sports, like even as a little kid, you’re not allowed to play flag football, or do P. E., or run around… Because we knew that that wasn’t going to be a part of my social development or job prospects later in life, my mom and dad pushed me into arts and music.

I more seriously got into art closer to the end of high school… Then in college, … the first couple months of being at UCLA, … I started kind of embracing my disabled and queer identities a lot more… Getting more in touch with those identities and gaining online friendships with queer and disabled artists really pushed me to start focusing on my artwork. In November of 2019, I started my Etsy shop and started drawing more regularly, especially with digital art. I eventually…joined OutWrite, and started doing portraits and things for articles in 2019.

GV: Now that you’re a fourth year, you’re on the cusp of graduating, you’re involved in the Disabled Student Union (DSU), you’re the Editor-in-Chief of OutWrite, which is also very historic because you are both trans/queer and disabled. So for your fourth year, how is this all culminating?

CI: Oh, my goodness, you sound like my mum. I’ll say I’m confident I’m not sure. But there have been a few opportunities recently that hopefully kind of speak to how my fourth year is gonna go, which I hope is well. For example, in April of this last year, I was contacted by the tech-accessories brand CASETiFY [for their Pride Month 2022 collection]… It’s just luck that I got to be able to participate in that and [now I’ve released] my own personal design collection… Also, right before summer, one of the writers who works for the UCLA College of Letters and Sciences, reached out and was like, “Hey, we’re doing profiles on graduating seniors who we find exceptional,” and he let me do it, even though I [wasn’t] a graduating senior. Opportunities just kind of come at you and you just have to take them as soon as you get them, so they don’t slip through your fingers.

I’m hoping the opportunities that I’ve gotten over the past three years, as an artist and an activist, will translate to me hopefully being welcomed into a workplace or a creative environment that values my voice as a trans and disabled person. Because I know, on my resume, I can’t erase the fact that…OutWrite is a queer organization, or the Disabled Student Union is a disabled organization, and that’s like two of the biggest things that I’ve worked on in my life. A lot of job tips for disabled people online always say to “prefer not to say” on the disability self-disclosure button, and stuff like that. But I’m always like: if I’m going to be breaking my back, figuratively or literally, for a company, being a production assistant (or an unpaid intern, or whatever), [the company] better accept me being disabled and being trans, or why the hell would I want to work there. I have the privilege as someone who is not in poverty, and someone who is not struggling financially, to choose to be in an environment that accepts me. That is one of the biggest privileges that I’ve experienced, even though I am disabled and I am trans, and if I have that choice, I’m not going to throw it away… Hopefully, the fact that I do have that privilege to be visible, and to be accepted in these environments, [I will be able to] open it up to people who don’t have that privilege at this moment, and hopefully, that’ll do some good.

GV: On a less professional side … How has your gender story/timeline and sexuality timeline intersected with disability? What is your relationship between the two of them?

CI: Totally. I’m sure you’ve probably heard this from the previous people you’ve interviewed (I’d be surprised if you haven’t). To me, my experiences with gender and sexuality and disability are pretty much like sisters, you know what I mean? So I don’t think I would have the same experience with gender and sexuality as I do now, if I was not born disabled.

A story that I typically tell about this specific topic is, as I said, I was born with a chronic illness, and I was diagnosed really, really young. That came with being separated from people, like kids my age for various circumstances. Like I said earlier, for physical activity or things that could be potentially dangerous to me… That social isolation at such an early age really started to separate me from the “traditional” socialization that boys and girls go through.

Beginning my life separated from typical kids, or nondisabled kids, fundamentally altered how I thought about myself. What I mean by that is that I didn’t have a concept of my gender identity until I was close to high school. I never thought of myself as a little girl or like someone who should hang out with little girls. I had a mix of friends from different genders, and I had fun with all of them, and as a little kid, I had really short haircuts; when you look at pictures of me from elementary school, or before, I look like a little boy. Being separated from those roles because I wasn’t…forced into them in school obviously affects how I then viewed my gender later in life. Related to that, both of my parents got degrees in hard sciences, my mom did sports, my mom did art, she did all of these types of things. She never forced me into a feminine gender role; she used to run after boys who would insult her [when she was growing up]… So, having that opportunity where your parents are not strictly into gender roles and kind of just raise you to be as strong as you can and to stand up for yourself, that also messes with how you’re “supposed to be socialized” when you’re a woman, right? All of that weird gender soup (or gender-less soup) kind of led to me not having any awareness surrounding my gender as I realized my queerness in middle school.

When I got in trouble eventually [for having a girlfriend] and caught for it, I still had that perception because my mom never expressed to me like, “I am upset at you for dating a girl,” it was always like, “You’re not supposed to have a girlfriend, you’re 12,” so I just kind of was queer. There was never any sort of realization or coming out that it was like, “I was straight before,” but that kind of also extended into gender in high school. I’ve never really been in a particularly feminine gender role — I never really dressed traditionally femininely, I wouldn’t wear dresses or skirts and when I would, I only did them for band. I would wear pretty shapeless jeans and hoodies for most of my life. When I was 16, the summer before my junior year, I got a bunch of hand-me-downs from my older sister who is quite feminine. I started acting more feminine and pushing myself into that gender role and wearing more feminine clothing. At that point, I was like, “Whoa,” my brain was like, “What, what the fuck is this, you’ve literally never done this before, and I hate it.” That summer is when I realized I was like, “Oh, maybe this whole time of not expressing myself in this way and not feeling any connection to femininity or like an identity of being a girl, being something,” and that summer I came out as a trans man. I have no memory of when I first heard the word “trans.” It wasn’t like I saw Miles McKenna on a YouTube video and I thought that “this was me.” Similarly to being queer, starting in middle school it just kind of came to me and it stuck. So I would say that kind of casual transition between perceived cis-ness and perceived straightness into a queer and trans identity wouldn’t have been so smooth and nonchalant and free of a lot of dysphoria actually, if I wasn’t brought up the way that I was because I was a disabled kid.

GV: How do neopronouns kind of come into play for you?

CI: The main reason why I felt connected to [xe/xem] was the concept of voidpunk… it’s knowing that you have been kind of dehumanized and alienated from typical society, whether that be on the basis of gender or sexuality or disability — it’s typically used by people who are aromantic or trans or disabled/neurodivergent. Instead of trying to prove your humanity to a world that has discarded you because you don’t fit into what it expects of you, you embrace being the alien or being the monster or being the non-normative being that they are afraid of you being.

I just feel like in every piece of media that has aliens in it, it’s always like the Planet Xenon, or Xenomorph, — the root “xeno-” means alien, so — the look and feel of xe/xem to me felt very alien, it felt very otherworldly. I actually was interviewed about neopronouns [by OutWrite], and my answer is really still the same. When I first discovered the pronouns, I hadn’t really become as in touch with my disability as a part of my identity at that point. But definitely now I feel that a big part of that alienation that I experienced, probably bigger than my transness and my queerness (although it does, as I said, go hand in hand), is the fact that I am visibly disabled. Like, the literal name of somebody who has Marfan syndrome is a Marfanoid, which is like, “That’s just an alien term. You just made that up.” So my literal body does not look how a human expects it to look, which is why I am the subject of staring. As I mentioned at the beginning of the interview, my access needs, the way that I see (where I squint), or I make a little fucking telescope with my hand in order to see things, there’s no way to escape me being weird, and not weird in like a Tumblr Rawr XD sense, but weird in a way that my body fundamentally contradicts what it means to be human, and what it means to be attractive or successful to a typical person who is not disabled, and who is not trans, and who is not queer.

So yeah, I would definitely say neopronouns helped me express that I am not simply in the spectrum of male to female that a lot of people see queer and genderqueerness as. I am on my own little planet, or my own little star somewhere else, and I think that’s really beautiful.

GV: Going on to the different part of LGBTQIA+: Aromantic. How does that specifically play into all of your intersections?

CI: I identified on the ace/aro spectrum during high school, but I didn’t really realize exactly what I was until college. That’s when I started identifying as aromantic [specifically alloaro]. It basically means I don’t experience romantic attraction. That is another thing that kind of alienates me from a typical society because even in the queer community, a lot of it is all about love and marriage and finding fulfillment within a partner, and that’s beautiful for a lot of people who experience that… This is called amatonormativity,…the expectation that your end goal is to find yourself in a loving romantic relationship, typically with a cishet partner.

That expectation bleeds itself into pretty much everything, right? A lot of cultures force you to get married, or if you don’t get married, you are kicked out of a family. The entire genre of rom-coms and how that influences how people see relationships, that somehow you are broken if you don’t have the desire to get into relationships, or if you focus on yourself, you’re selfish or pathologized as a narcissist, or something like that. If you want to look into more of arophobia or aphobia in general, Yasmin Benoit, she’s a Black, aroace activist/model from Britain, and she has a lot of posts with reactions to her content as an asexual person. There’s some that are specific to aromantic and the responses that she gets from people on Twitter, and it’s basically like, “Oh, so you’re a psychopath,” or, “Oh, you were abused as a child, so now you don’t want to be in a relationship,” or like, “What are you doing with your life if you’re not looking for [love],” “You’re an empty sort of person because you’re not fulfilled by another, your other half.” So, yeah, I would say being aromantic is a big part of my queer identity, it’s probably the biggest part of my sexuality, at least at this point. I do truly feel like if I was not in a relationship, or any sort of intimate relationship, whether that be sexual or romantic, I would be okay, and I am perfectly fulfilled doing what I love without there having to be a specific person that I am in love with most of all.

GV: July is obviously Disability Pride Month. How do you feel about it being a month?

CI: That’s a good question. I think it is interesting, because when you look into the history of why they chose July, it’s because George Bush signed the ADA into law in 1990, and it’s like, “Congrats, George Bush, as if you’ve never done anything bad ever.” I do like the concept of us having a Pride month; I feel like every month has six different celebrations that are month long, so I think it’s okay that we have a month … maybe moving it to something that’s not July and not focused around praising a government for doing something for us when the government has left us behind in literally every other way, maybe that could be an improvement.

I do think there needs to be more work surrounding Disability Pride Month. Like, it shouldn’t be something that only disabled people know about. There’s a good tweet by this activist called Mary Fashik, she’s under the username Upgrade Accessibility, and she had this tweet on the day before Disability Pride Month this year and it said, “There will be no flashy merchandise. Companies won’t be changing their logos. Celebrities won’t be posting on social media about it. And the disabled community still won’t have equity or equality.” Not that I want corporate disability pride, but the fact that the United States government and institutions don’t even acknowledge their inaccessibility is baffling, like a lot of people don’t know anything about disability history, they don’t even realize that they’re being inaccessible. The reason they don’t realize they’re being inaccessible is because it’s impossible for disabled people to literally, or figuratively, get a seat at the table because there’s a flight of stairs to get to the table, you know what I mean? It’s not like disability needs are even considered, and there’s huge, monumental oppression of disabled people, like that it’s legal to pay disabled people less than a minimum wage. If you’re on disability benefits, you can’t get married without losing those benefits, and you might lose life-saving care. Buildings don’t have to fix their inaccessibility, according to the ADA, unless they are doing a major remodeling… The majority of schools are segregated between disabled kids and nondisabled kids, and those disabled kids, especially if they have intellectual or developmental disabilities, are abused in schools and are not treated with the same level of humanity as other kids… People think that institutions are where disabled people, mentally or otherwise, get help, and [these institutions] are so rife with abuse and harm to disabled people because people don’t see those patients as fully human… That oppression exists, and it just continues to persist.

It’s beautiful that we have disability pride, and that we can celebrate ourselves in our bodies. It’s beautiful that we have this opportunity to celebrate ourselves, and I think celebration of disability is a huge act of resistance in a world that has all of those oppressive systems. But unless Disability Pride Month and Disability Pride celebrations are doing something tangible for those of us that are the most vulnerable, then I don’t know if we’re deserving of it yet. You know, June is Pride Month because Stonewall happened during June and Stonewall was a monumental push for queer rights, and it was led by the most vulnerable for the most vulnerable.

There have been so many instances of disability history, like I said, 504 Sit-in of 1977, the “Capitol Crawl” in 1990 that pushed then President Bush to sign the ADA, there have been historic acts of disability pride and disability resistance, resilience, and activism. The fact that only disabled people know about it is really — it’s criminal. There needs to be nondisabled people in those conversations, and not necessarily to give their own opinion, but to sit back and listen, so that they can use their privilege to amplify our voices instead of stifling them. A lot of people are realizing now that the state can just invent what it means to be disabled. Like, even just thinking, homosexuality was considered a mental illness, and as soon as they can have a medical justification for why you are the way you are, they can lock you up, or back in earlier times when enslaved people would try to escape, they pathologized the idea of, “If you are an enslaved person and you want to escape, you have a mental illness, we’re just going to lock you up.” The people in power can just pathologize marginalized peoples to become a disability… With the recent overturn of Roe v. Wade, Imani Barbarin talks a lot about, to warn people, that not only can you become disabled at any time (because you can get into a car accident or something like that or have a stroke), but that you can become disabled at any time because the state can decide that you are now disabled.

GV: When I watched “Crip Camp” because I took Disability Studies 101W, that was the first time that I realized I knew a lot about disability, but I had no clue that some of this stuff happened, you know, like, literally people,

CI: Like people who couldn’t walk, crawled up the Capitol steps. And I mean like, children and stuff. I’m like, “Oh, my God, that’s metal.”

GV: Why is Disability Pride important to you?

CI: I would say a big part personally is with my specific disability. Marfan syndrome is a rare disease and throughout my entire life, I’ve always been The Kid, specifically, with Marfan syndrome. When I was a little kid (well wasn’t really little, I was also very tall), and when other shorter kids would come up to me and be like, “Why are you so tall?” and I was like five or six, so I would go into the whole explanation of what Marfan is… I’ve been quite literally a poster child for my own disability for my entire life. That in and of itself, little six-year-old me, educating kids and parents about my disability and what to look out for, like, that’s a form of activism, and of course, as a little kid, you don’t call yourself an activist.

Disability pride, to me, is having the opportunity to express my disability and the struggles I have with it, and the joys that I have with it, and have it be received kind of with open loving arms. Of course, we’re not at that point yet where people feel completely comfortable talking about disability… Whenever people hear disabled, they kind of cringe like it’s something that they shouldn’t be saying, and that it’s taking away something from a person if they identify that way. As someone who’s been living with an illness my whole life, I no longer want the first question people ask me to ask: “if you could take a magic pill, would you cure your disability?” That should not be the first thing that people think when they see a disabled person, they should not be thinking, “how can I make this person able-bodied like I am?” I want that first question to be genuine curiosity about why there is something that you might not understand.

The most beautiful thing is when I tell someone that I have Marfan syndrome, and they go, “Oh, like Jonathan Larson,” or some people have given actors and singers I’ve never even heard of before. I was like, “They do? Troye Sivan has Marfan syndrome? What do you mean?” Like, those beautiful little moments of like, “Oh, I know exactly what you’re talking about. Please tell me more,” you know, “I’m genuinely interested in this and I genuinely care.” Disability Pride is really a road to that, a road to caring, and is and should be a road to fighting against all of those horrific, oppressive systems that keep us down in the United States and beyond.

I want disabled kids to be able to traverse the world without having to be that activist. They should just know that their body is different in whatever way that they may have limitations, but that does not make them a burden. That does not make them less of a person or less worthy of love or support. Until we can get to a point where all disabled people feel worthy of that care, then I don’t think that there will be a time when Disability Pride is obsolete, but we’re obviously not at that point yet. Hopefully, we’re getting closer, and hopefully, more people are seeing visibly disabled people like myself and thinking, “Hey, he looks like me. Maybe it’s not all bad.”

You can find Christopher’s content on his Instagram and TikTok, shop his artwork on Etsy or CASETiFY, or look at his portfolio on his website.

Credits:

Author: Giulianna Vicente (She/Her)

Copy Editors: Emma Blakely (They/She/He), Bella (She/They)